As a museum curator, I develop dynamic history exhibitions and public programs for public enrichment regarding the African American experience in the West.

Museum Exhibitions.

No Justice, No Peace: LA 1992

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising, CAAM presents No Justice, No Peace: LA 1992, an exhibition that examines one of the most notorious episodes of urban unrest in American history...

No justice, No Peace: LA 1992

On March 3, 1991, Rodney King led the California Highway Patrol on a high-speed chase that concluded with a struggle, during which some officers beat King with their batons. The brutality in the videotaped arrest sent shockwaves around the world and enraged many in the already-frustrated African American community in LA. On April 29, 1992, when a predominantly white jury acquitted the four officers accused in King’s beating, rage turned to violence.

No Justice, No Peace: LA 1992 looks back at crucial episodes in Los Angeles history that influenced the quality of life for African Americans and other communities of color over the course of fifty years. These include the second wave of the Great Migration of the 1940s, during which African Americans fled the harsh realities of the South, seeking employment and opportunity after World War II; the rising racial tensions between Mexican Americans and law enforcement heightened by the Zoot Suit Riots (1943) and Bloody Christmas (1951); and the legislative achievements of the Civil Rights Movement that shaped African American expectations for equality in the 1960s, but were slighted by the reality of unequal housing practices and discrimination.

The unjust treatment and oppressive conditions created by the overwhelming presence of law enforcement in black communities would create the worst civil rebellion the country had ever seen to date: the Watts Rebellion of 1965. In light of the strained political climate after this cataclysmic event, the City of Los Angeles made efforts to counter negative representations and move toward

equality in political representation through the election of its first African American mayor, former police officer Tom Bradley, in 1973.

Despite the presence of a black mayor, communities of color were still left to confront their contentious relationship with law enforcement during the War on Drugs overseen by the Reagan Administration. Throughout the 1980s, Los Angeles saw the hyper-criminalization of black citizens and aggressive responses by the police department, which sought to curb drug possession and dealing. These interactions incited violent drug raids such as 39th and Dalton that highlighted the pervasive nature of the LAPD’s excessive use of force. This continued to lay the groundwork for the compounding animosity towards law enforcement that seeped into the 1990s, leading ultimately to the 1992 Los Angeles Uprisings.

With powerful photographs, videos, historic documents, posters, flyers, and other ephemera, No Justice, No Peace: LA 1992 considers decades of complex socio-political history that have contributed to underlying tensions among Los Angeles’s marginalized groups and communities, and it sheds light on race relations, socioeconomics, and equality in America today.

This exhibition was curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager.

Photos: Brian Forrest

Center Stage: African American Women in Silent Race Films

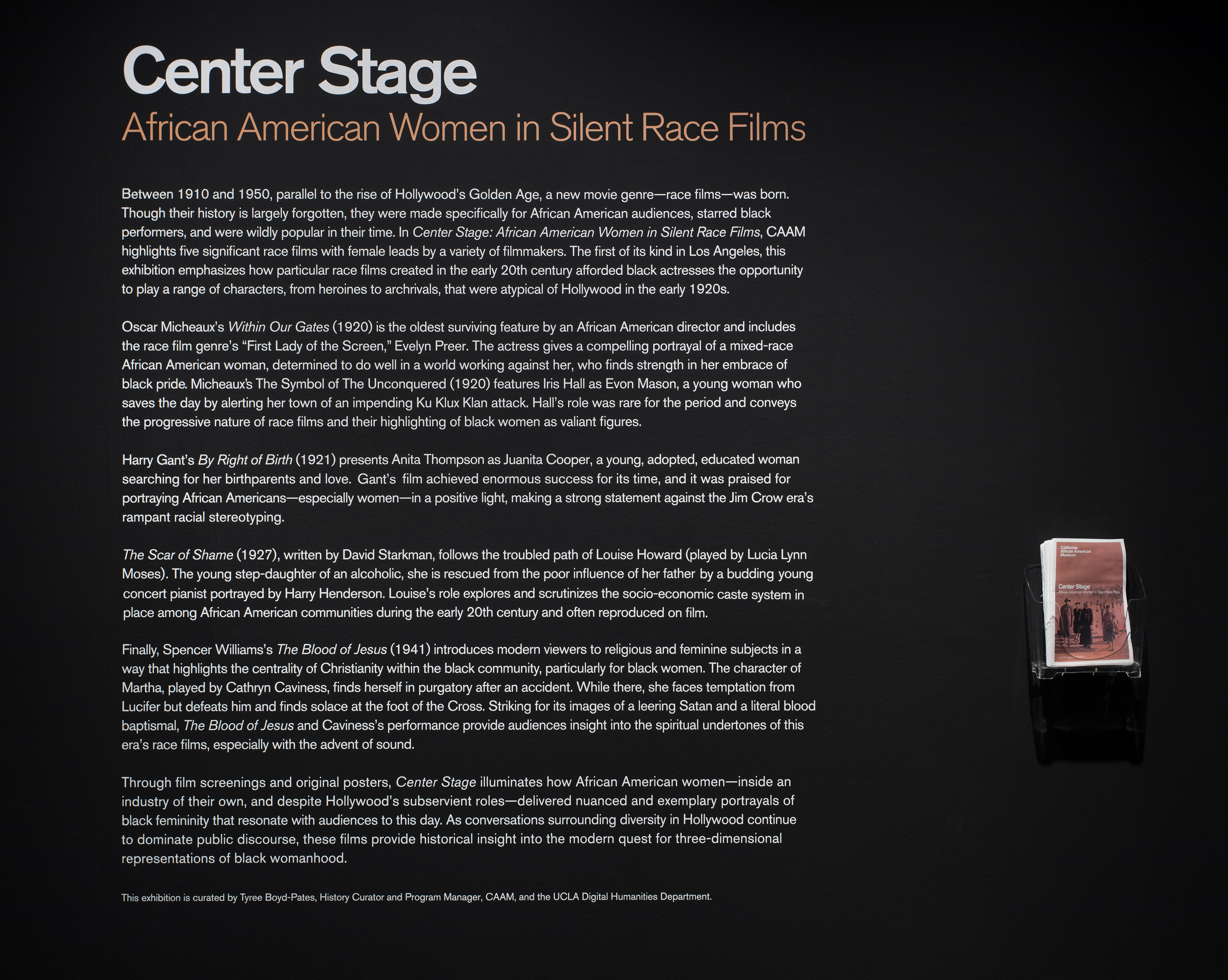

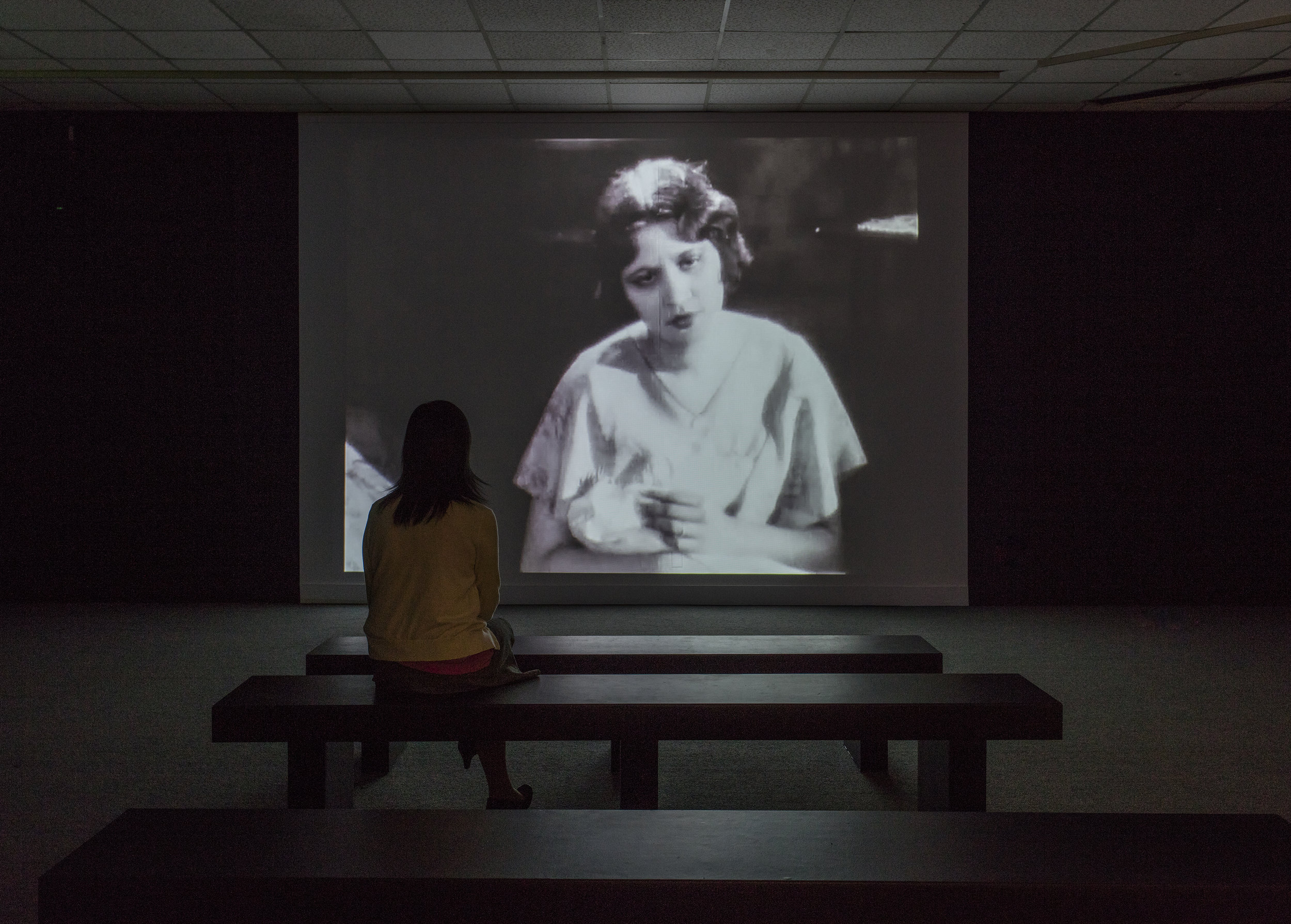

Between 1910 and 1950, parallel to the rise of Hollywood’s Golden Age, a new movie genre — race films — was born. Though their history is largely forgotten, they were made specifically for African American audiences, starred black performers, and were wildly popular in their time...

Center Stage: African American Women in Silent Race Films

In Center Stage: African American Women in Silent Race Films, CAAM highlights five significant race films with female leads by a variety of filmmakers. The first of its kind in Los Angeles, this exhibition emphasizes how particular race films created in the early 20th century afforded black actresses the opportunity to play a range of characters, from heroines to archrivals, that were atypical of Hollywood in the early 1920s.

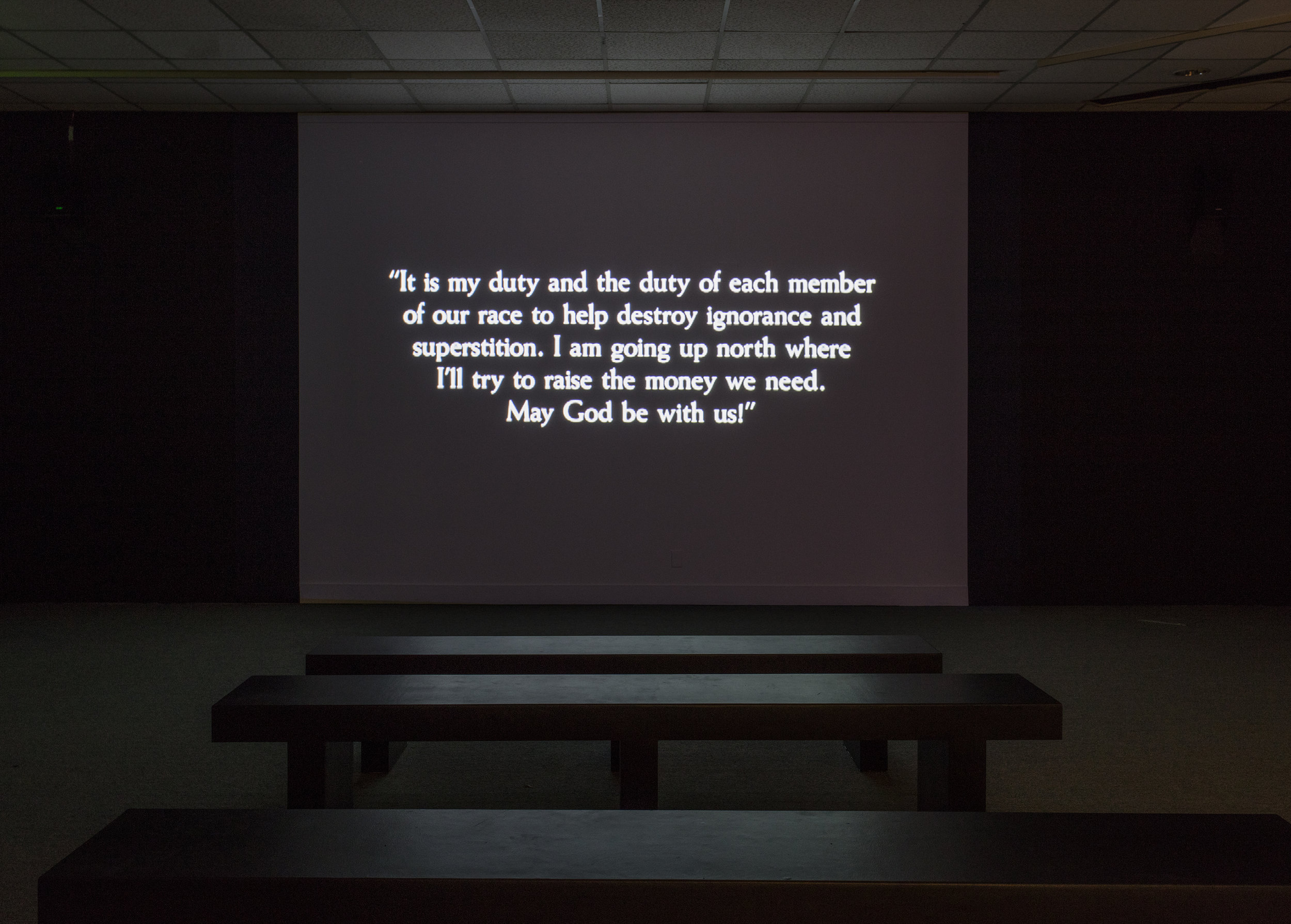

Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920) is the oldest surviving feature by an African American director and includes the race film genre's "First Lady of the Screen," Evelyn Preer. The actress gives a compelling portrayal of a mixed-race African American woman, determined to do well in a world working against her, who finds strength in her embrace of black pride. Micheaux’s The Symbol of The Unconquered (1920) features Iris Hall as Evon Mason, a young woman who saves the day by alerting her town of an impending Ku Klux Klan attack. Hall’s role was rare for the period and conveys the progressive nature of race films and their highlighting of black women as valiant figures.

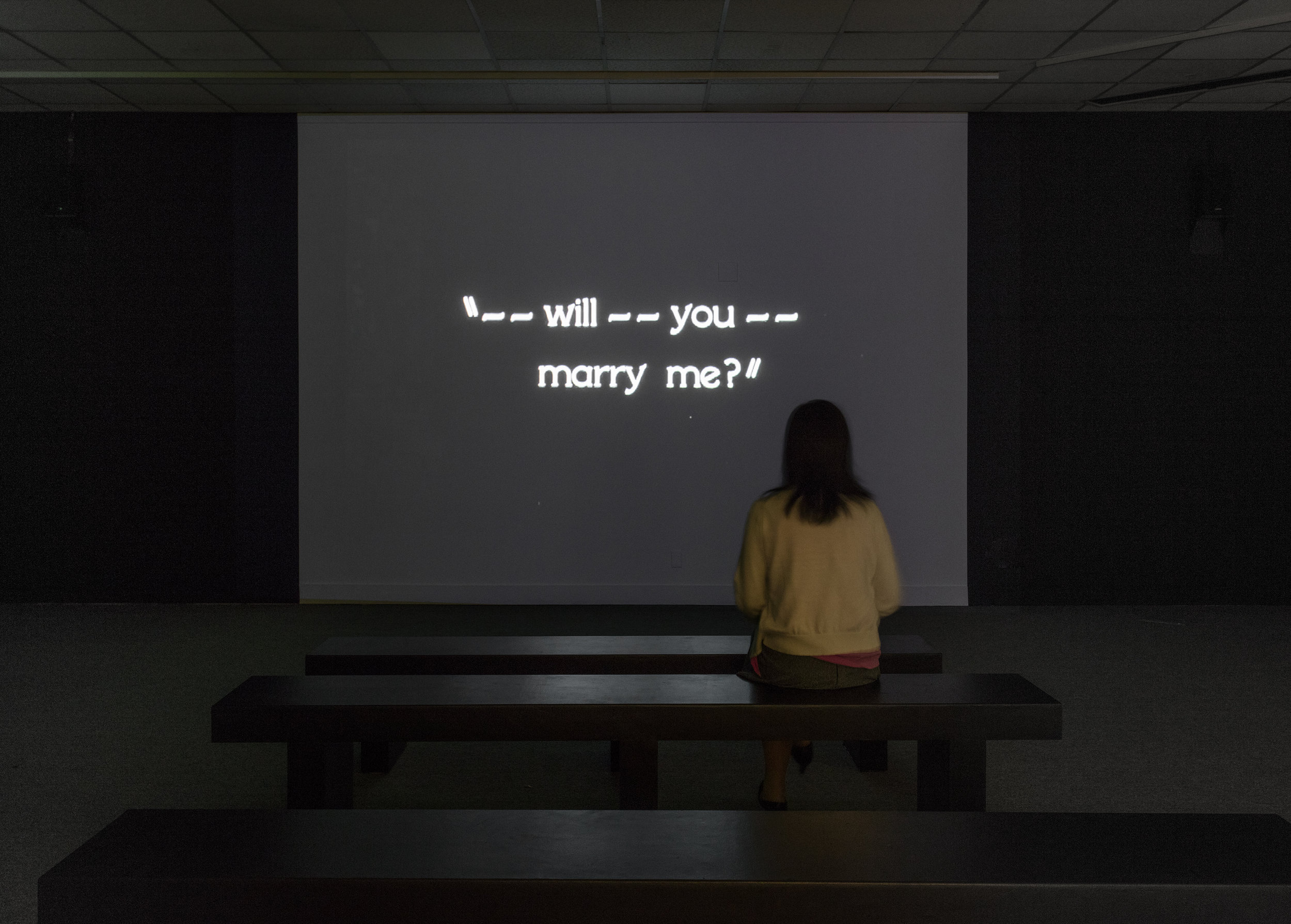

Harry Gant’s By Right of Birth (1921) presents Anita Thompson as Juanita Cooper, a young, adopted, educated woman searching for her birthparents and love. Gant’s film achieved enormous success for its time, and it was praised for portraying African Americans — especially women — in a positive light, making a strong statement against the Jim Crow era’s rampant racial stereotyping.

The Scar of Shame (1927), written by David Starkman, follows the troubled path of Louise Howard (played by Lucia Lynn Moses). The young step-daughter of an alcoholic, she is rescued from the poor influence of her father, a budding concert pianist portrayed by Alvin Hillyard. Louise's role explores and scrutinizes the socio-economic caste system in place among African American communities during the early 20th century and often reproduced on film.

Finally, Spencer Williams’s The Blood of Jesus (1941) introduces modern viewers to religious and feminine subjects in a way that highlights the centrality of Christianity within the black community, particularly for black women. The character of Martha, played by Cathryn Caviness, finds herself in purgatory after an accident. While there, she faces temptation from Lucifer but defeats him and finds solace at the foot of the Cross. Striking for its images of a leering Satan and a literal blood baptismal, The Blood of Jesus and Caviness’s performance provide audiences insight into the spiritual undertones of this era’s race films, especially with the advent of sound.

Through film screenings and original posters, Center Stage illuminates how African American women—inside an industry of their own, and despite Hollywood's subservient roles—delivered nuanced and exemplary portrayals of black femininity that resonate with audiences to this day. As conversations surrounding diversity in Hollywood continue to dominate public discourse, these films provide historical insight into the modern quest for three-dimensional representations of black womanhood.

This exhibition was curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager, CAAM, and the UCLA Digital Humanities Department.

Photos: Brian Forrest

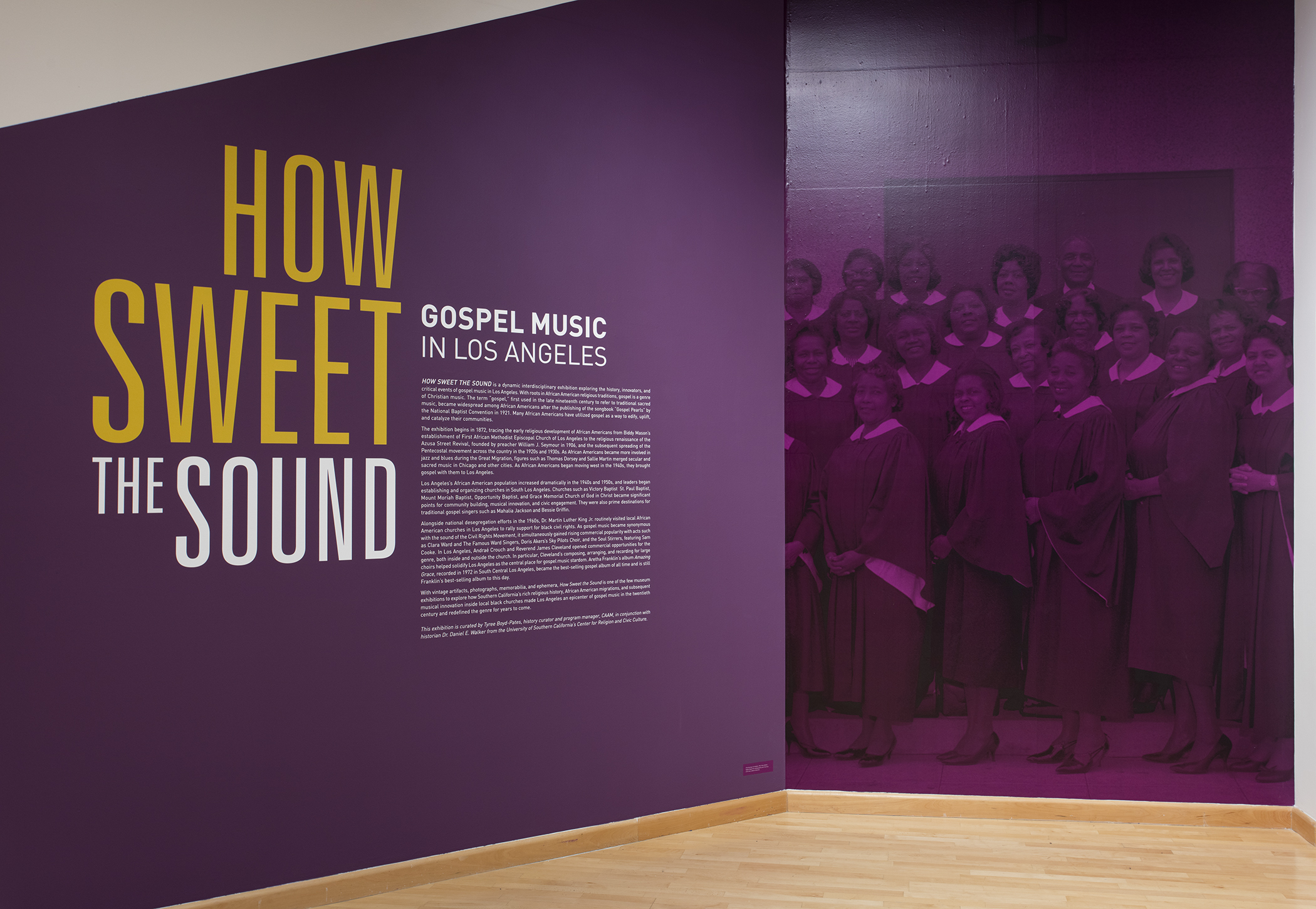

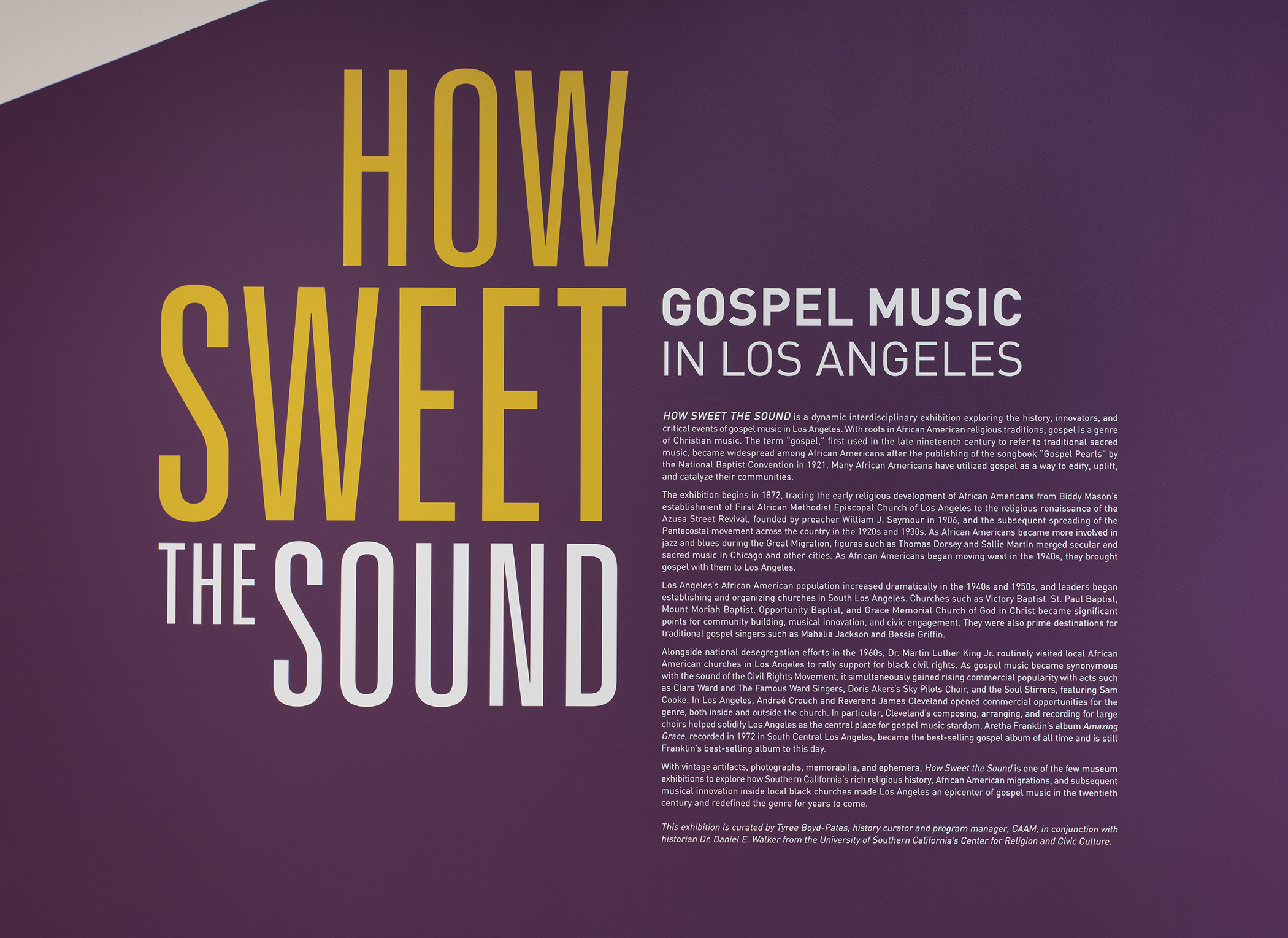

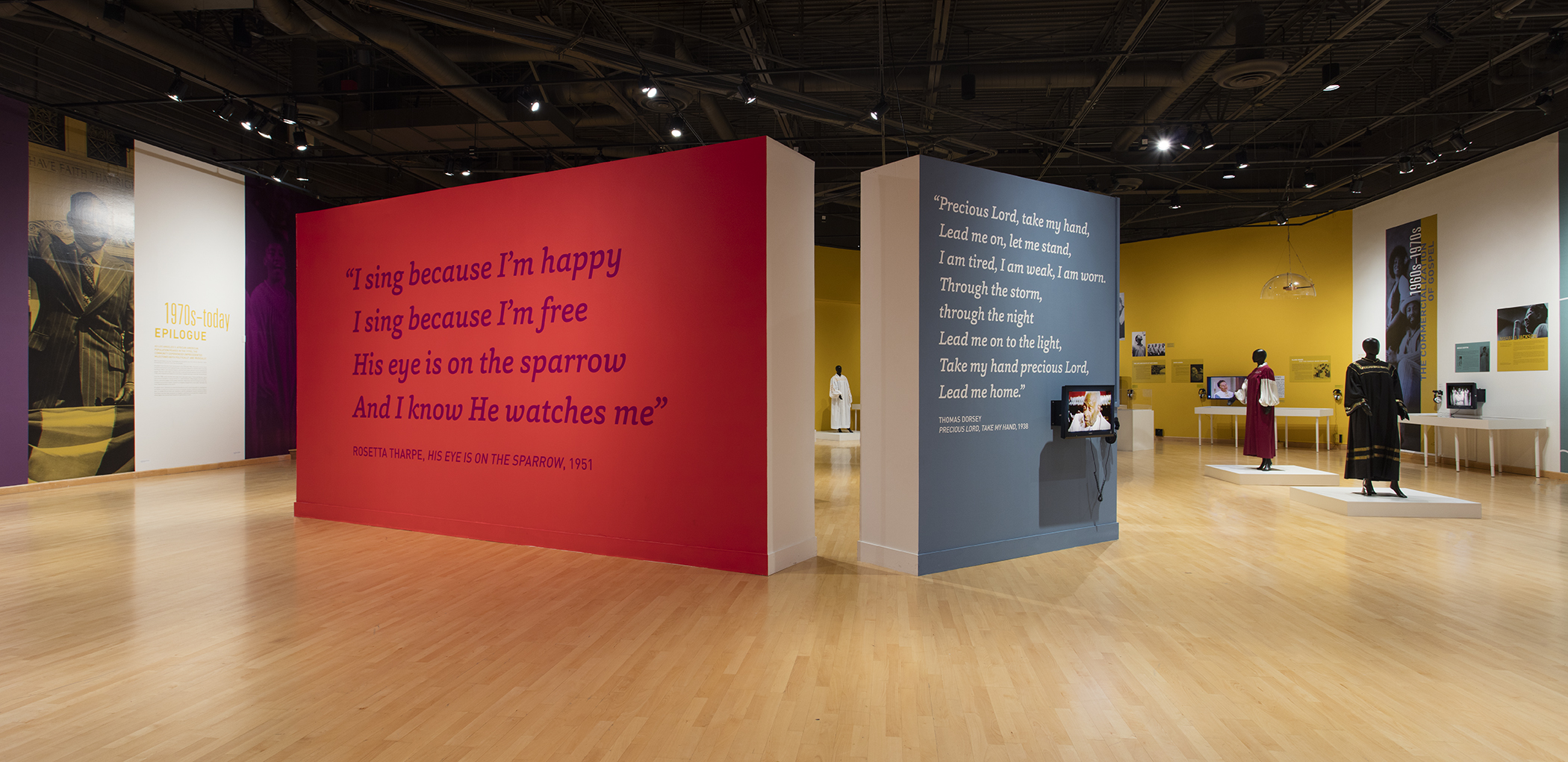

How Sweet The Sound: Gospel Music in Los Angeles

How Sweet the Sound is a dynamic interdisciplinary exhibition exploring the history, innovators, and critical events of gospel music in Los Angeles..

How Sweet The Sound: Gospel Music in Los Angeles

With roots in African American religious traditions, gospel is a genre of Christian music. The term “gospel,” first used in the late nineteenth century to refer to traditional sacred music, became widespread among African Americans after the publishing of the songbook “Gospel Pearls” by the National Baptist Convention in 1921. Many African Americans have utilized gospel as a way to edify, uplift, and catalyze their communities.

The exhibition begins in 1872, tracing the early religious development of African Americans from Biddy Mason’s establishment of First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles to the religious renaissance of the Azusa Street Revival, founded by preacher William J. Seymour in 1906, and the subsequent spreading of the Pentecostal movement across the country in the 1920s and 1930s. As African Americans became more involved in jazz and blues during the Great Migration, figures such as Thomas Dorsey and Sallie Martin merged secular and sacred music in Chicago and other cities. As African Americans began moving west in the 1940s, they brought gospel with them to Los Angeles.

Los Angeles’s African American population increased dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s, and leaders began establishing and organizing churches in South Los Angeles. Churches such as Victory Baptist, St. Paul Baptist, Mount Moriah Baptist, Opportunity Baptist, and Grace Memorial Church of God in Christ became significant points for community building, musical innovation, and civic engagement. They were also prime destinations for traditional gospel singers such as Mahalia Jackson and Bessie Griffin.

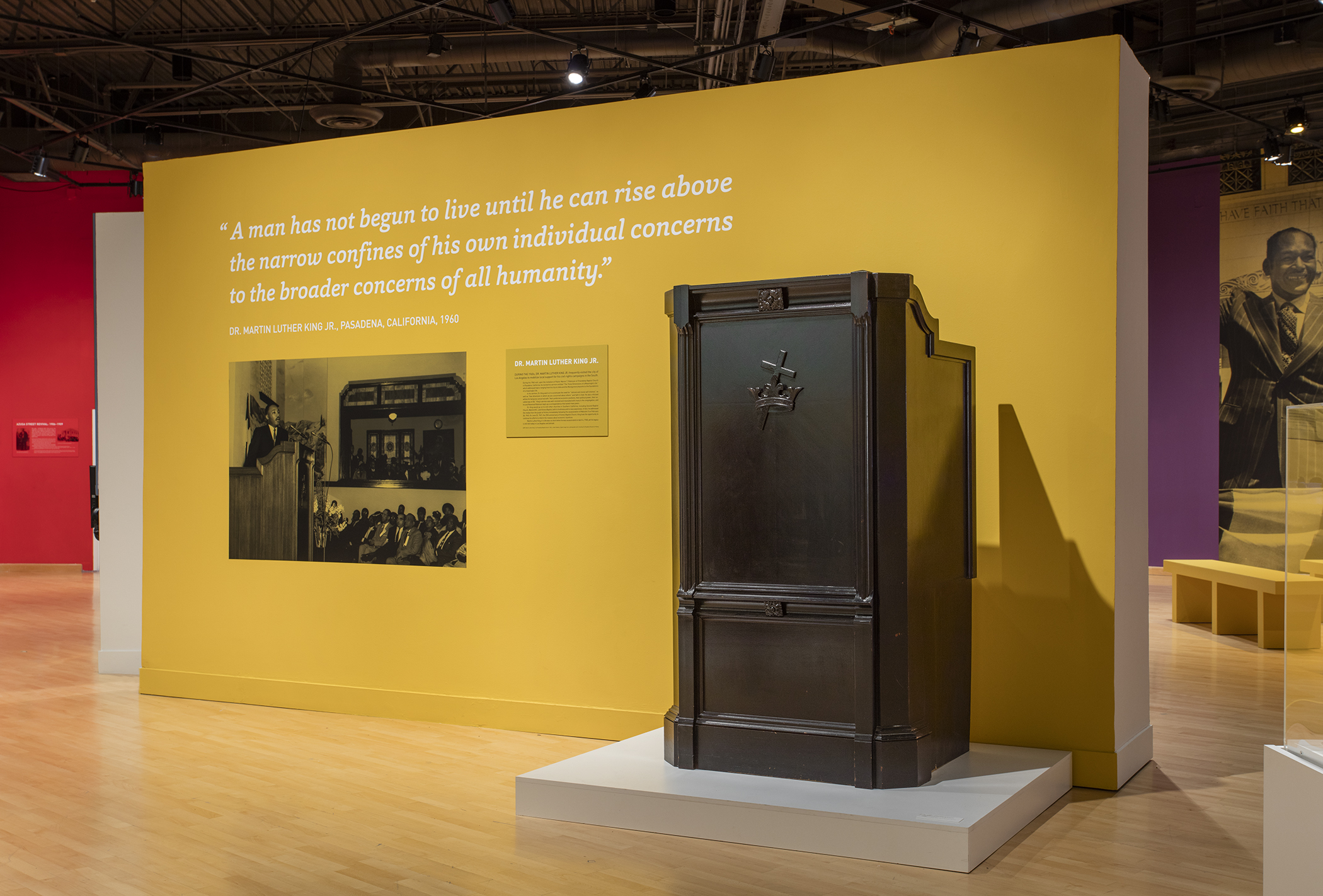

Alongside national desegregation efforts in the 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. routinely visited local African American churches in Los Angeles to rally support for black civil rights. As gospel music became synonymous with the sound of the Civil Rights Movement, it simultaneously gained rising commercial popularity with acts such as Clara Ward and The Famous Ward Singers, Doris Akers’s Sky Pilots Choir, and the Soul Stirrers, featuring Sam Cooke. In Los Angeles, Andraé Crouch and Reverend James Cleveland opened commercial opportunities for the genre, both inside and outside the church. In particular, Cleveland’s composing, arranging, and recording for large choirs helped solidify Los Angeles as the central place for gospel music stardom. Aretha Franklin’s album Amazing Grace, recorded in 1972 in South Central Los Angeles, became the best-selling gospel album of all time and is still Franklin’s best-selling album to this day.

With vintage artifacts, photographs, memorabilia, and ephemera, How Sweet the Sound is one of the few museum exhibitions to explore how Southern California’s rich religious history, African American migrations, and subsequent musical innovation inside local black churches made Los Angeles an epicenter of gospel music in the twentieth century and redefined the genre for years to come.

This exhibition is curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, history curator and program manager, CAAM, in conjunction with historian Dr. Daniel E. Walker from the University of Southern California’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

Photos: Brian Forrest

Watch

Los Angeles Freedom Rally, 1963

On Sunday, May 26, 1963, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to a crowd of over 30,000 people at Wrigley Field in South Los Angeles.

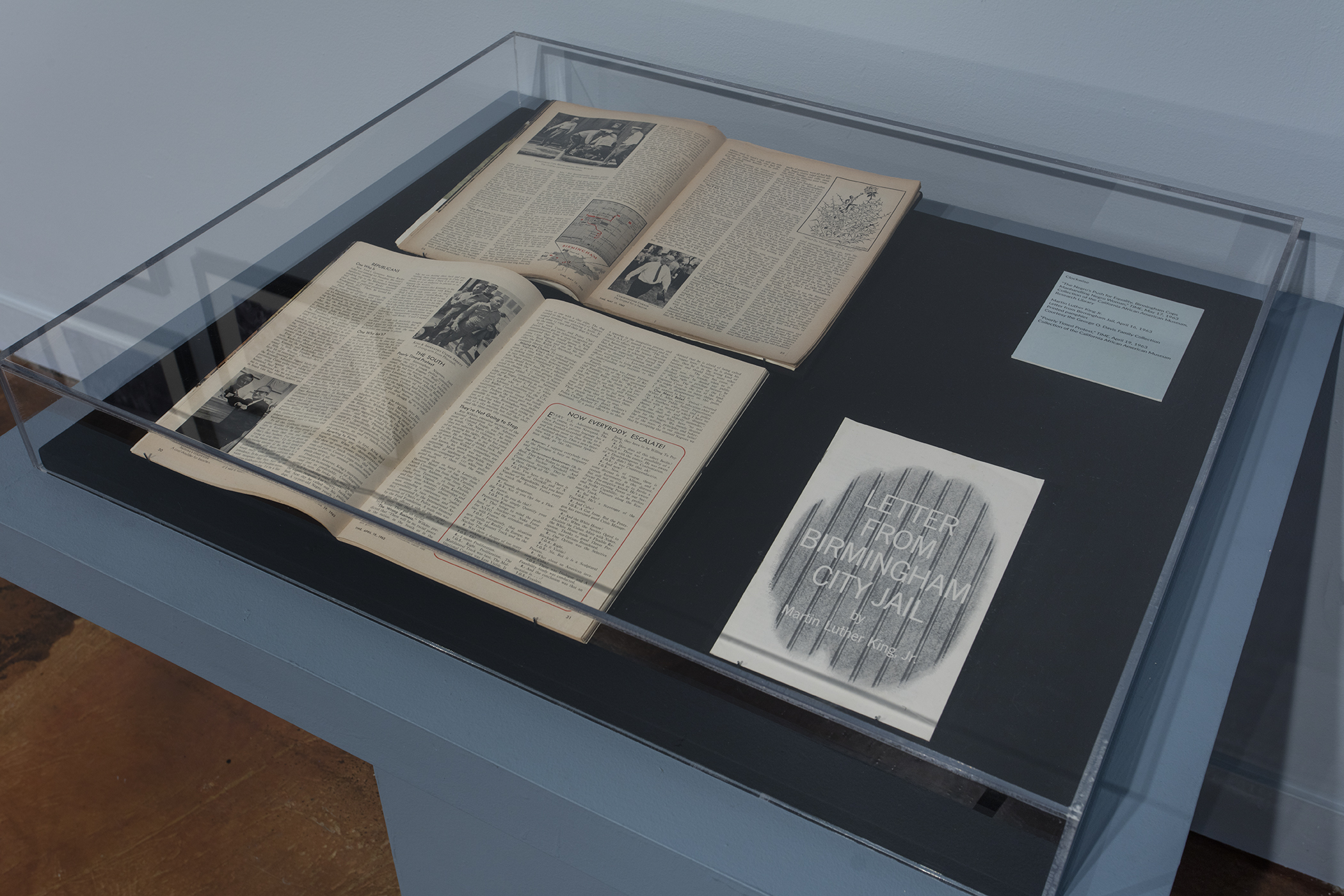

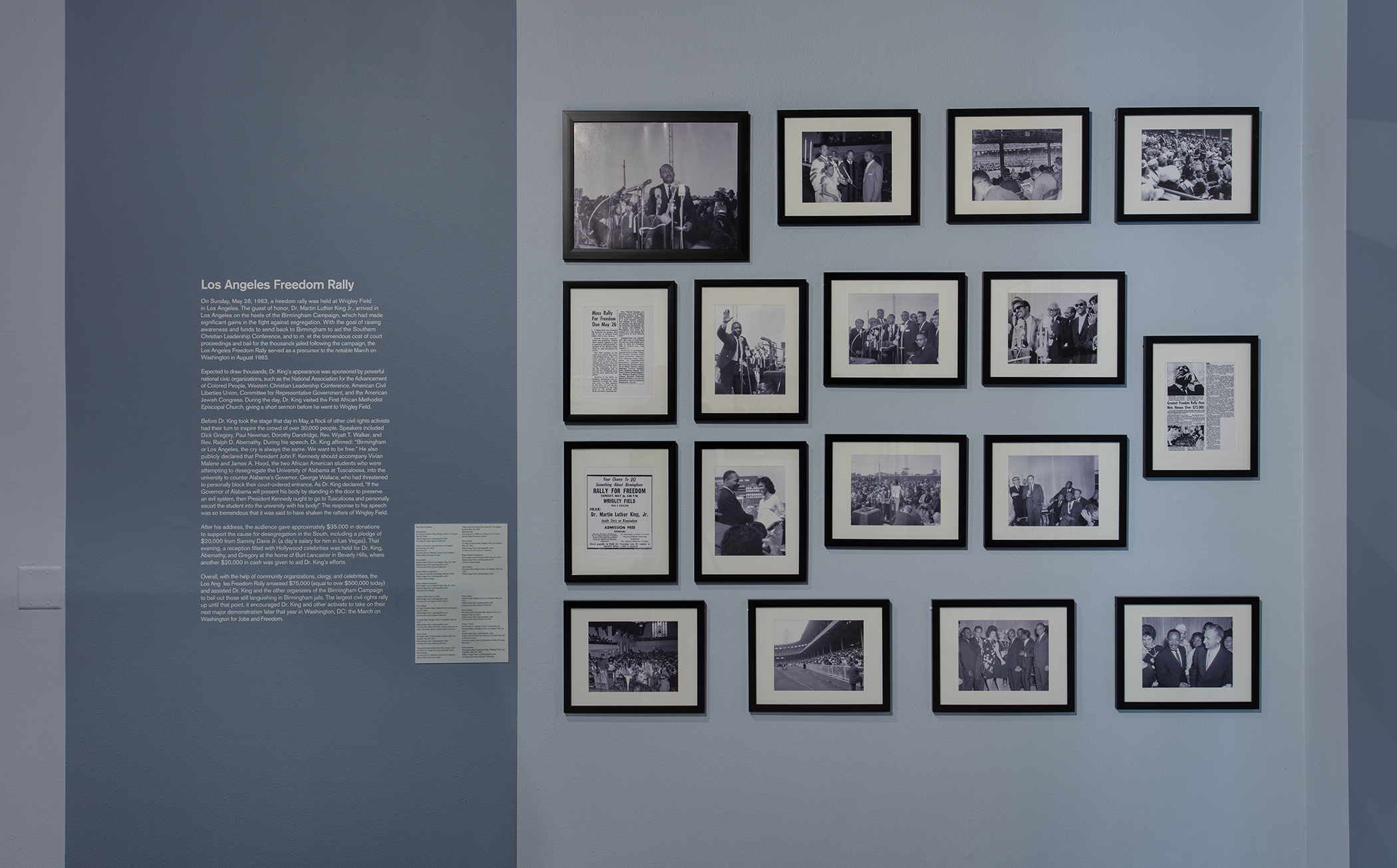

Los Angeles Freedom Rally, 1963

One of the largest civil rights rallies in the country, predating the famous March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom by three months, the Los Angeles Freedom Rally was held to support racial equality and fundraise for the struggle for integration in Birmingham, Alabama. Attracting celebrities Dorothy Dandridge, Rita Moreno, Paul Newman, Sammy Davis Jr., Dick Gregory, and other notable supporters of King, the event raised over half a million dollars.

On the occasion of its 55th anniversary, Los Angeles Freedom Rally, 1963 explores the critical historical events behind Dr. King’s major civil rights rally in Los Angeles, as well as subsequent developments that led to the passing of the groundbreaking Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

The exhibition explores numerous events in 1963 that had a significant impact on civil rights efforts nationwide. In the spring of 1963, Dr. King assisted in the organization of the Birmingham Campaign in Alabama, an effort by local black leaders to desegregate the city’s public spaces. During this campaign, Dr. King and other civil rights leaders assembled the Children’s Crusade, in which African American youth protested civil injustice and were met with brutal attacks by the Birmingham police force. Continuing to convert political opinion on the side of the Civil Rights Movement, and to raise funds for those jailed during the Birmingham Campaign, Los Angeles held its Freedom Rally at Wrigley Field, where Dr. King would serve as keynote speaker. The assassination in June 1963 of Medgar Evers, an activist and field secretary for the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People, further propelled leaders to convene and organize for a major demonstration in the nation's capital.

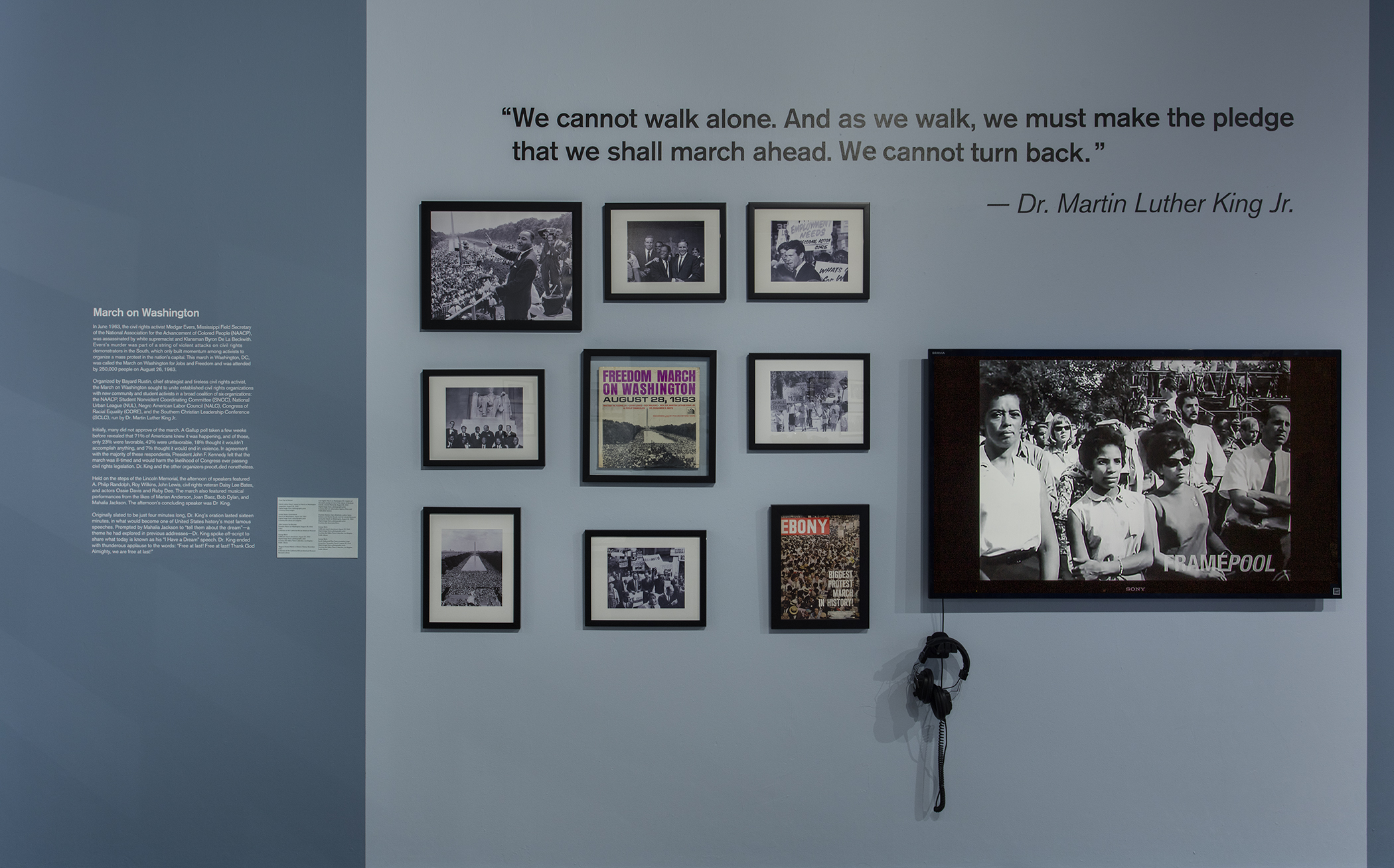

PrESS

Moreover, the exhibition chronicles the 1963 March on Washington, where Dr. King famously recited his “I Have a Dream” speech. Using the momentum from both these pivotal rallies, Sammy Davis Jr. enlisted the participation of Frank Sinatra and Count Basie, who used their celebrity to support the Civil Rights Movement. Celebrity endorsement, coupled with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy later that year, politically mobilized President Lyndon B. Johnson to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

With rare photographs by Los Angeles African American photographer Harry Adams (1918–1988), Los Angeles Freedom Rally, 1963 offers a unique look into Dr. King’s visits to Los Angeles, how Hollywood celebrities leveraged their influence to support desegregation and the crucial role that the Los Angeles Freedom Rally played in the fight for equality and civil rights.

This exhibition is curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager, and Taylor Bythewood-Porter, Assistant History Curator.

Special acknowledgment to Friendship Baptist Church of Pasadena; Keith Rice, Historian and Archivist of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge; Diane Lara and the family of Harry Adams; and to the exhibition lenders.

Photos: Brian Forrest

Watch

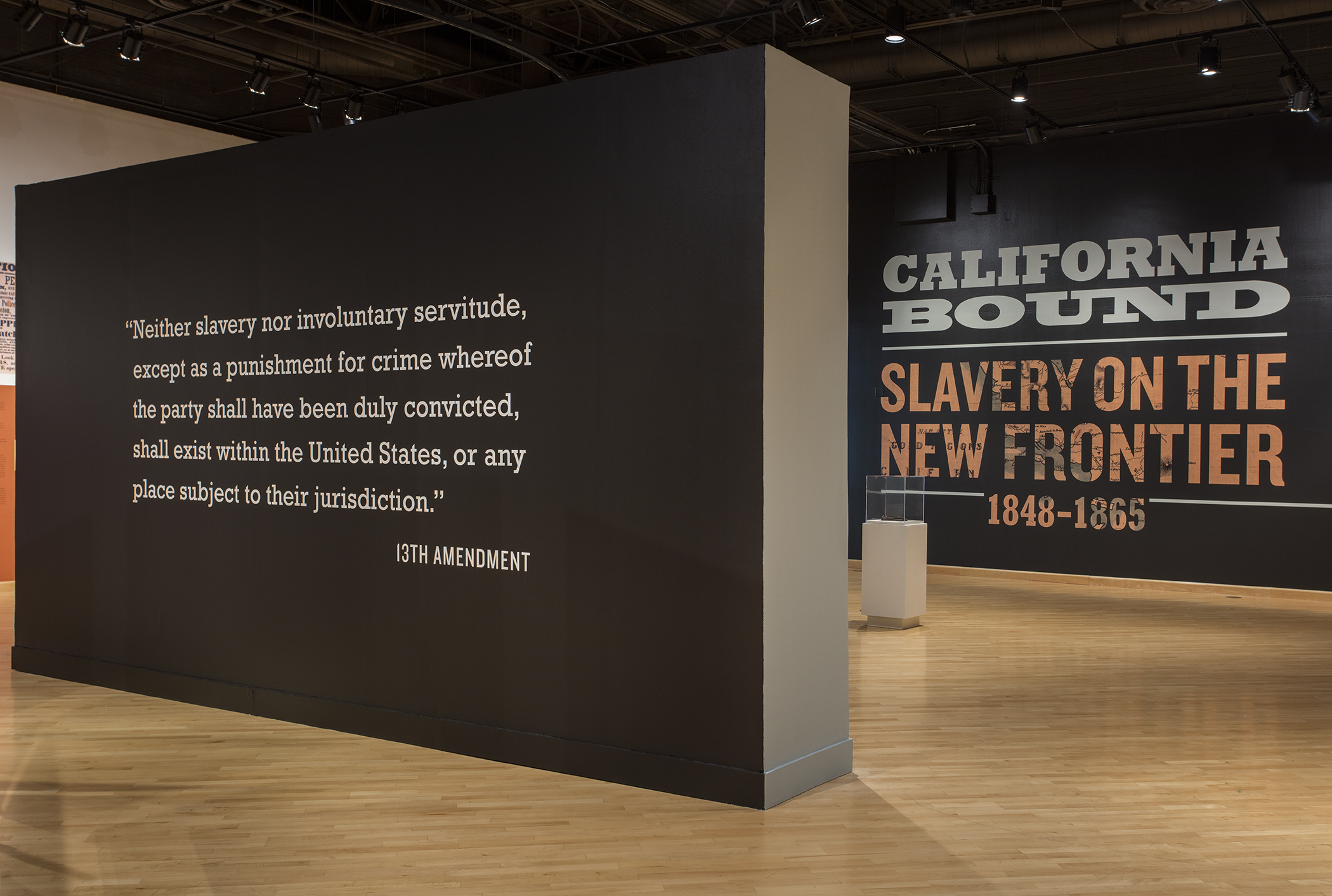

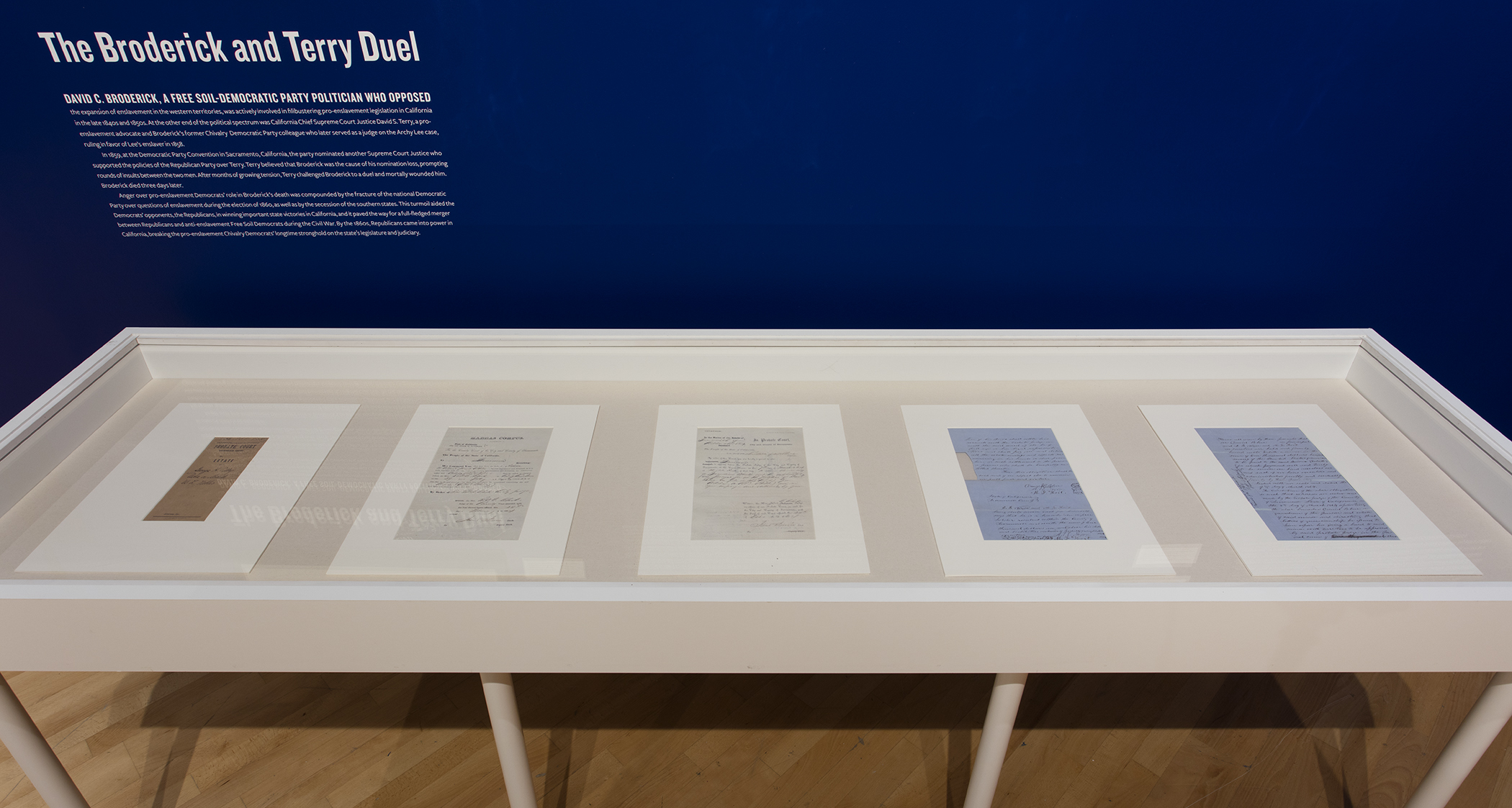

California Bound: Slavery on the New Frontier 1848 - 1868

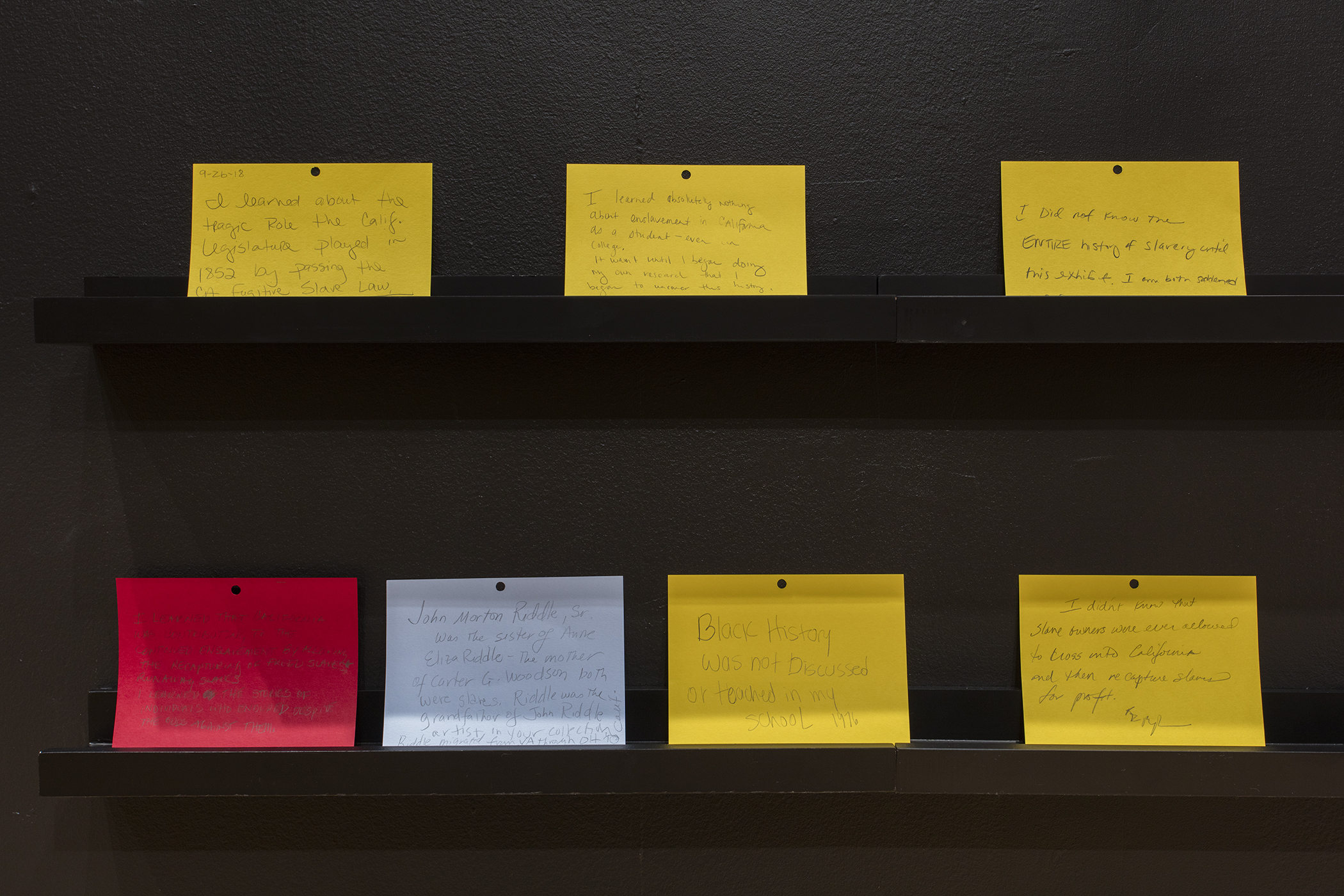

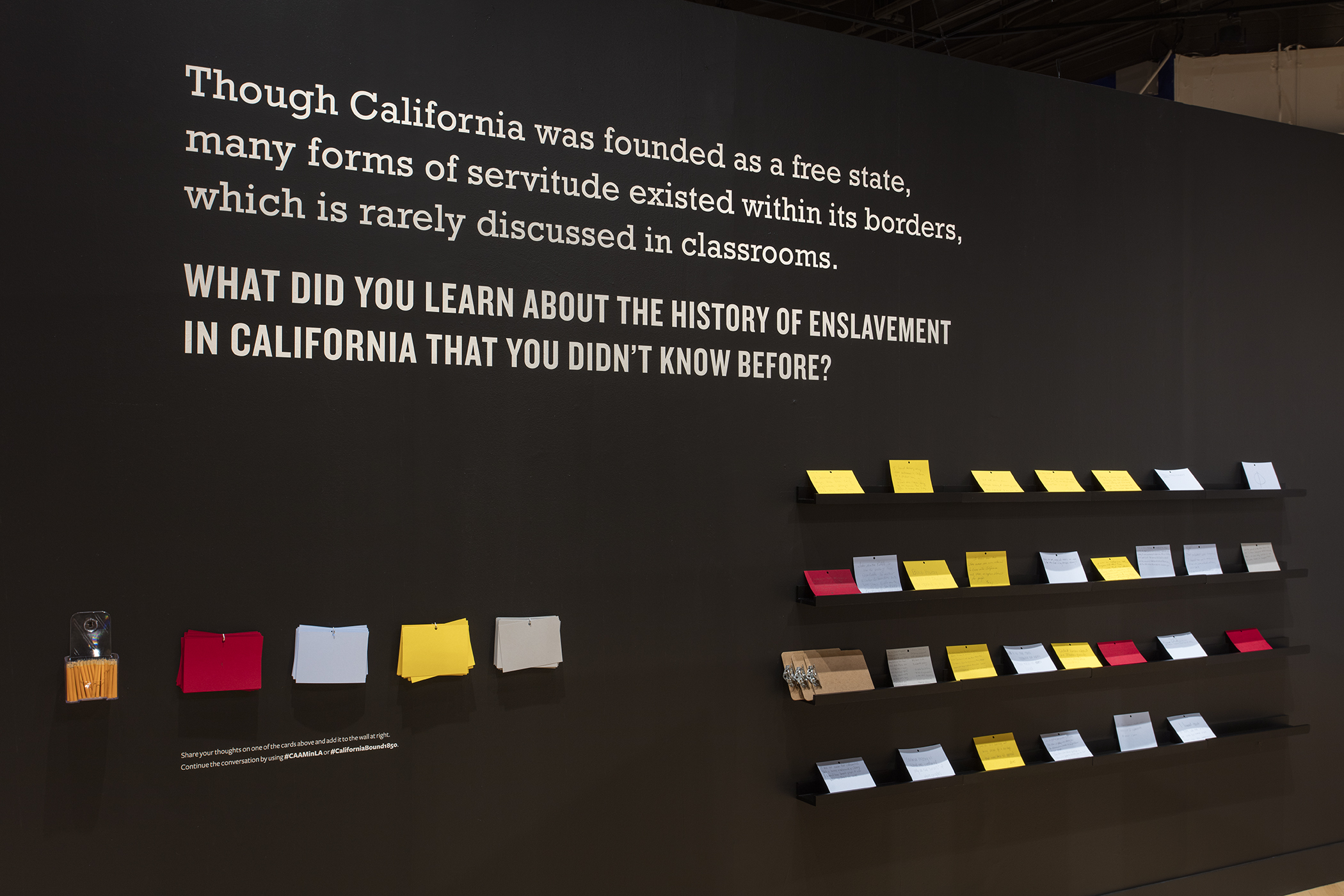

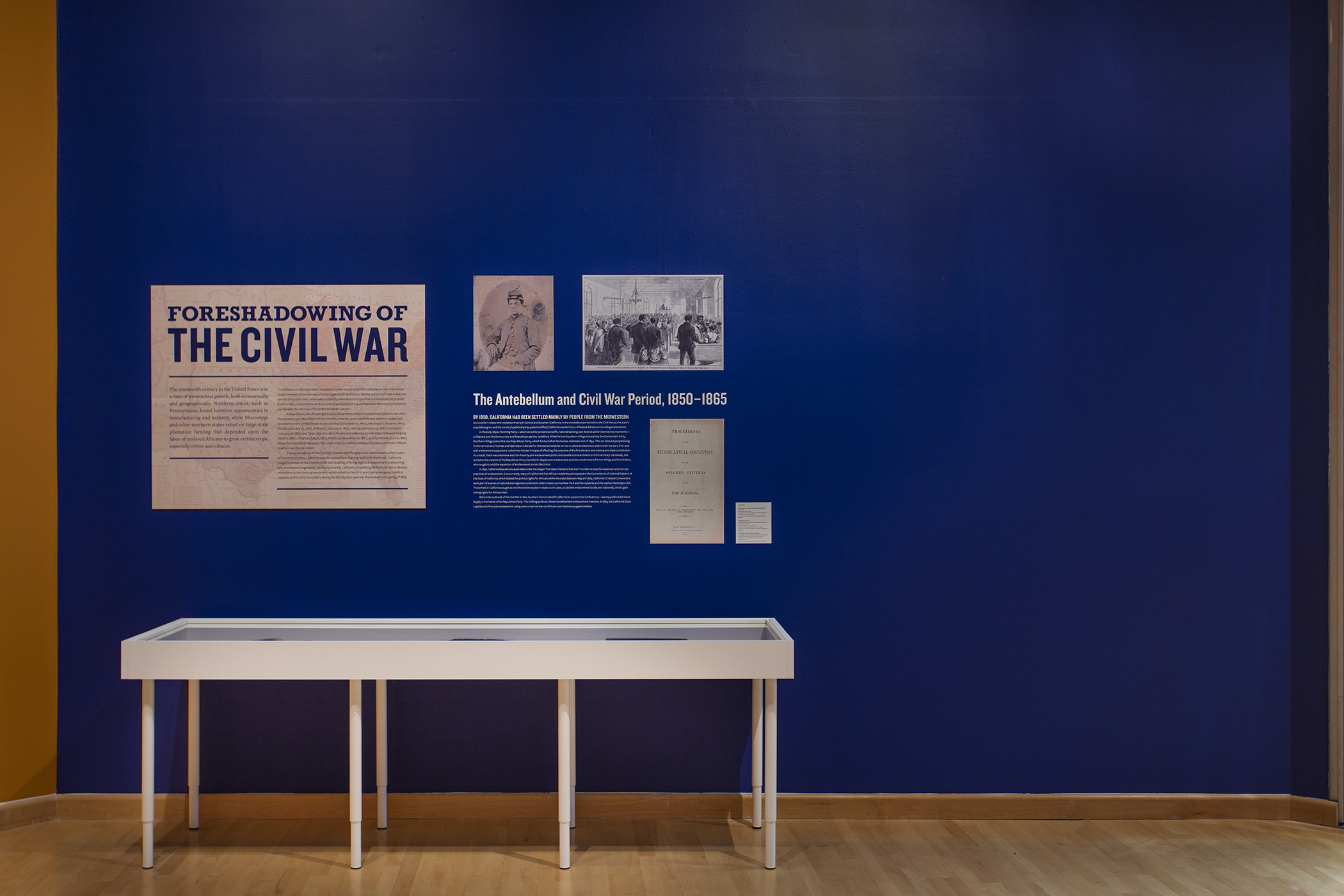

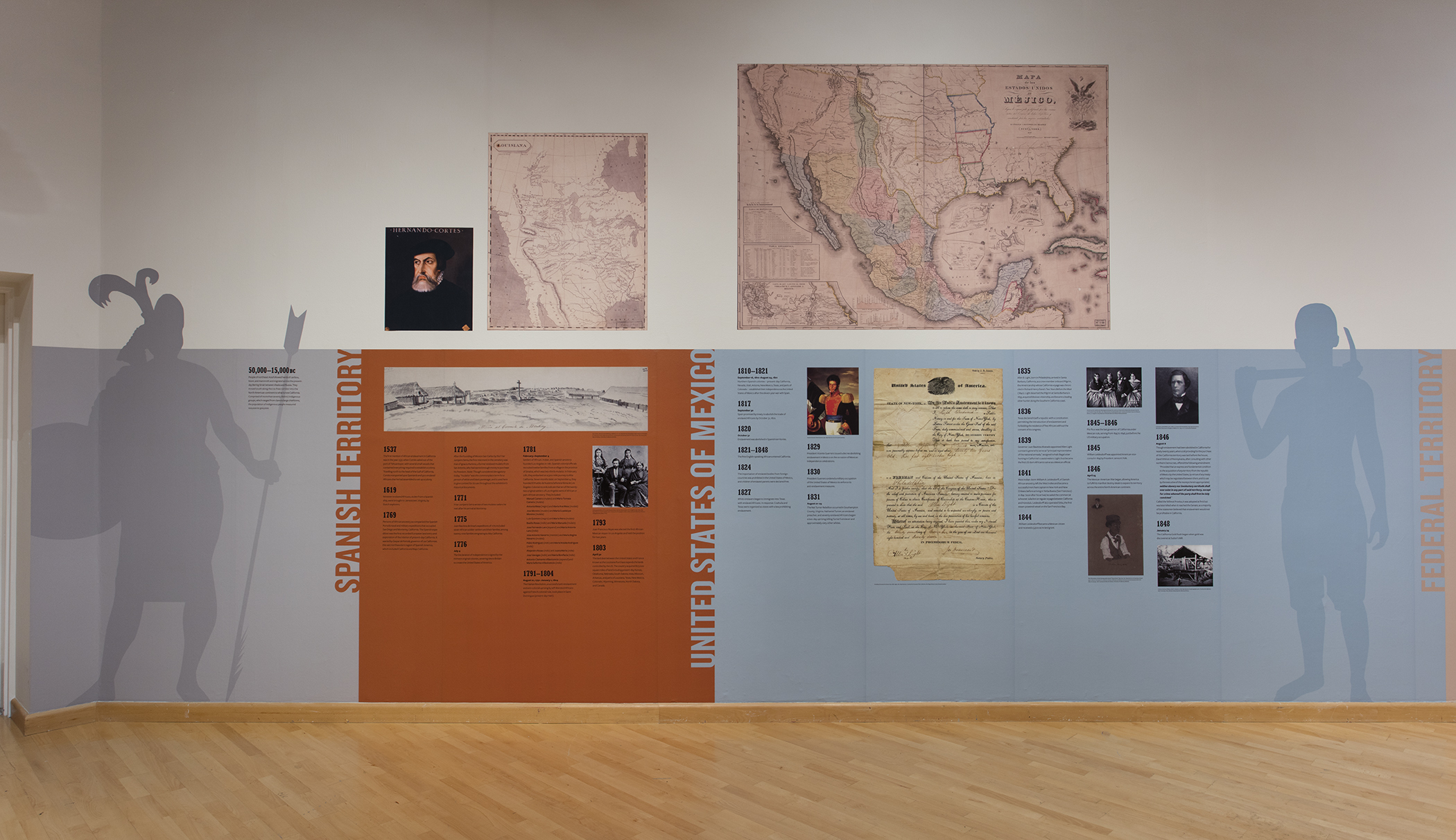

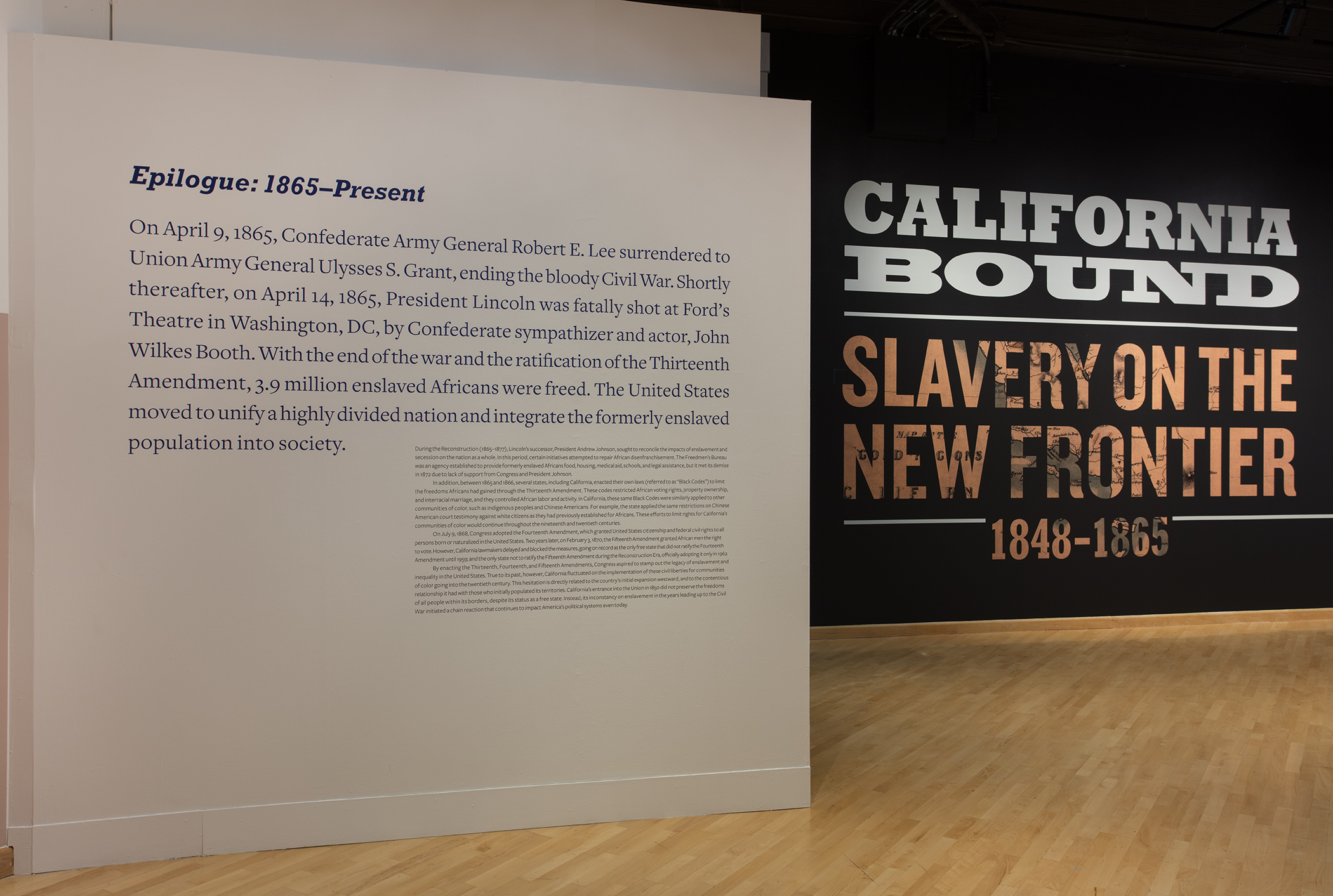

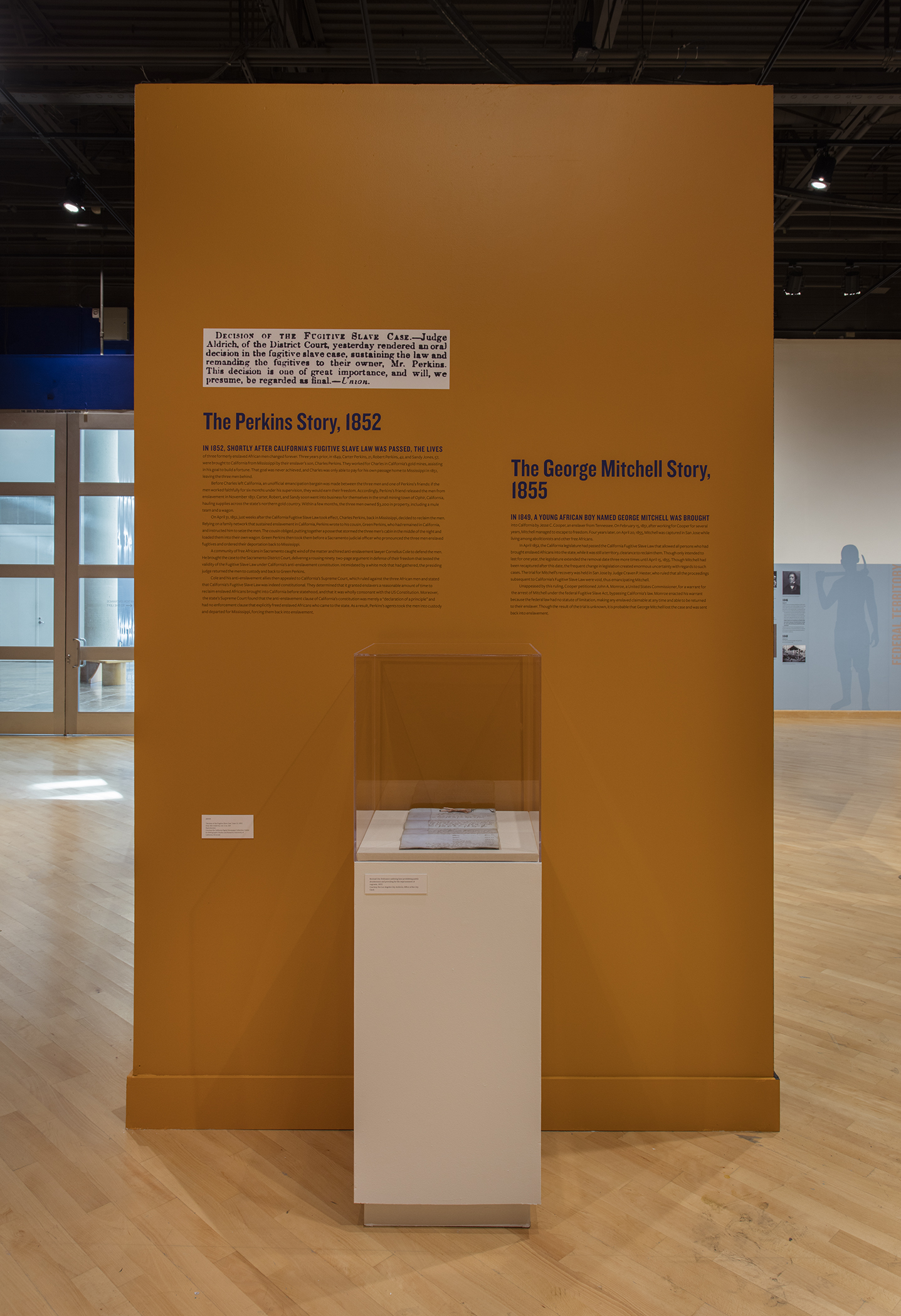

California Bound: Slavery on the New Frontier, 1848–1865 examines California’s underrecognized involvement with enslavement through legislation in the nineteenth century and looks back at crucial episodes in California’s history.

California Bound: Slavery on the New Frontier 1848 - 1868

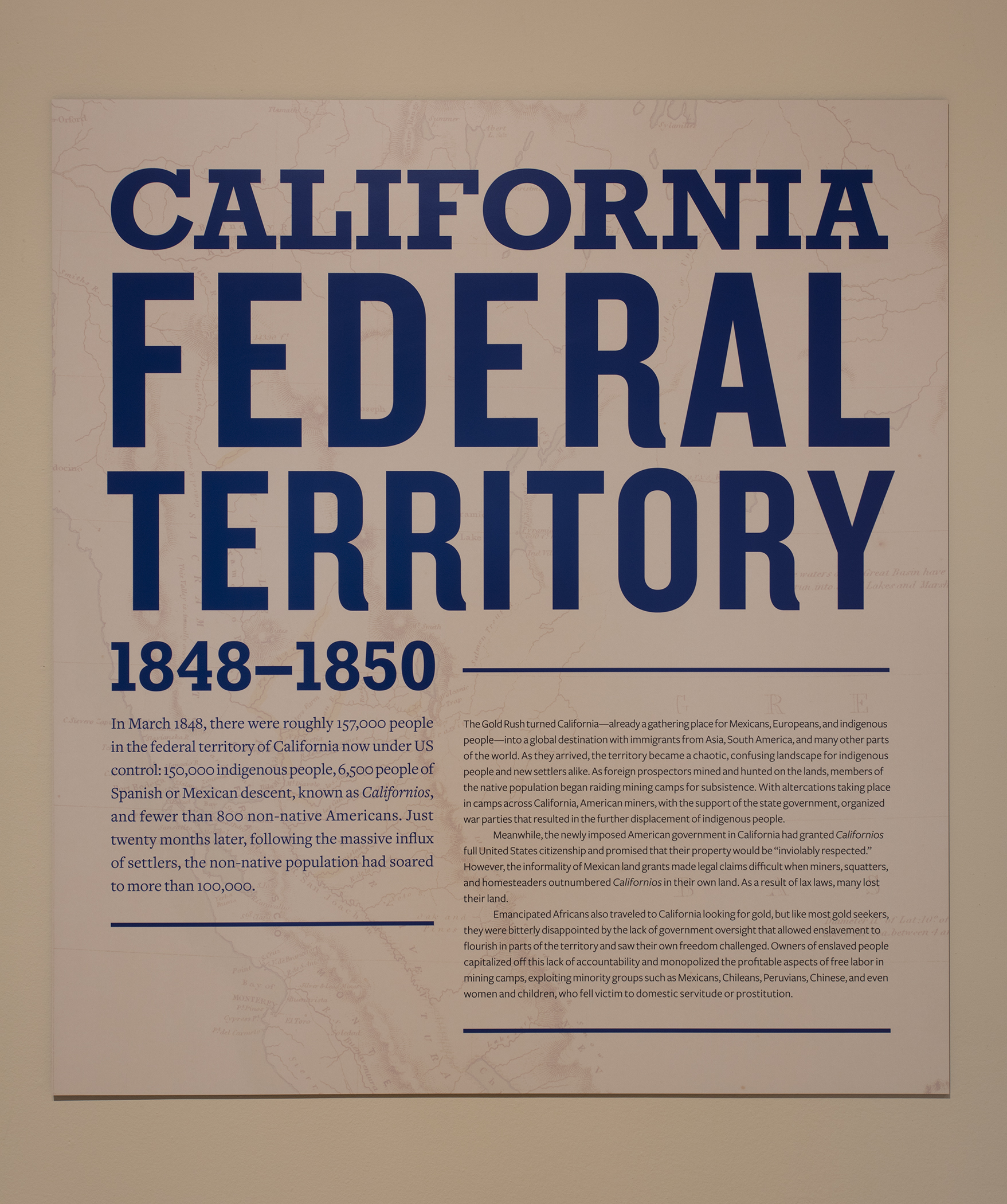

After centuries of Spanish colonization and Mexican-American conflicts over the region’s territory, the Gold Rush of 1848 created the largest single migration to California and helped initiate and reinforce color barriers between whites and non-whites.

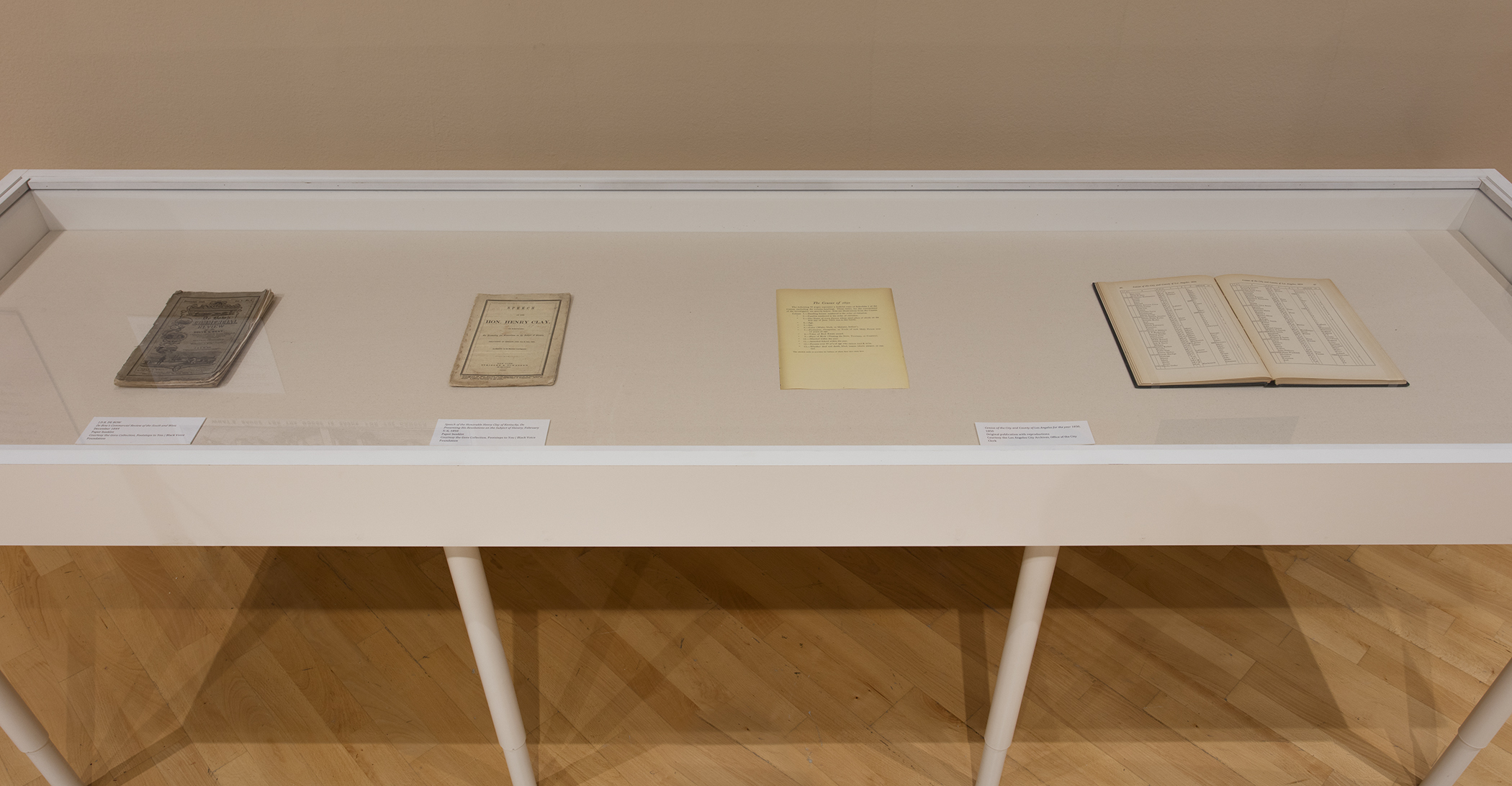

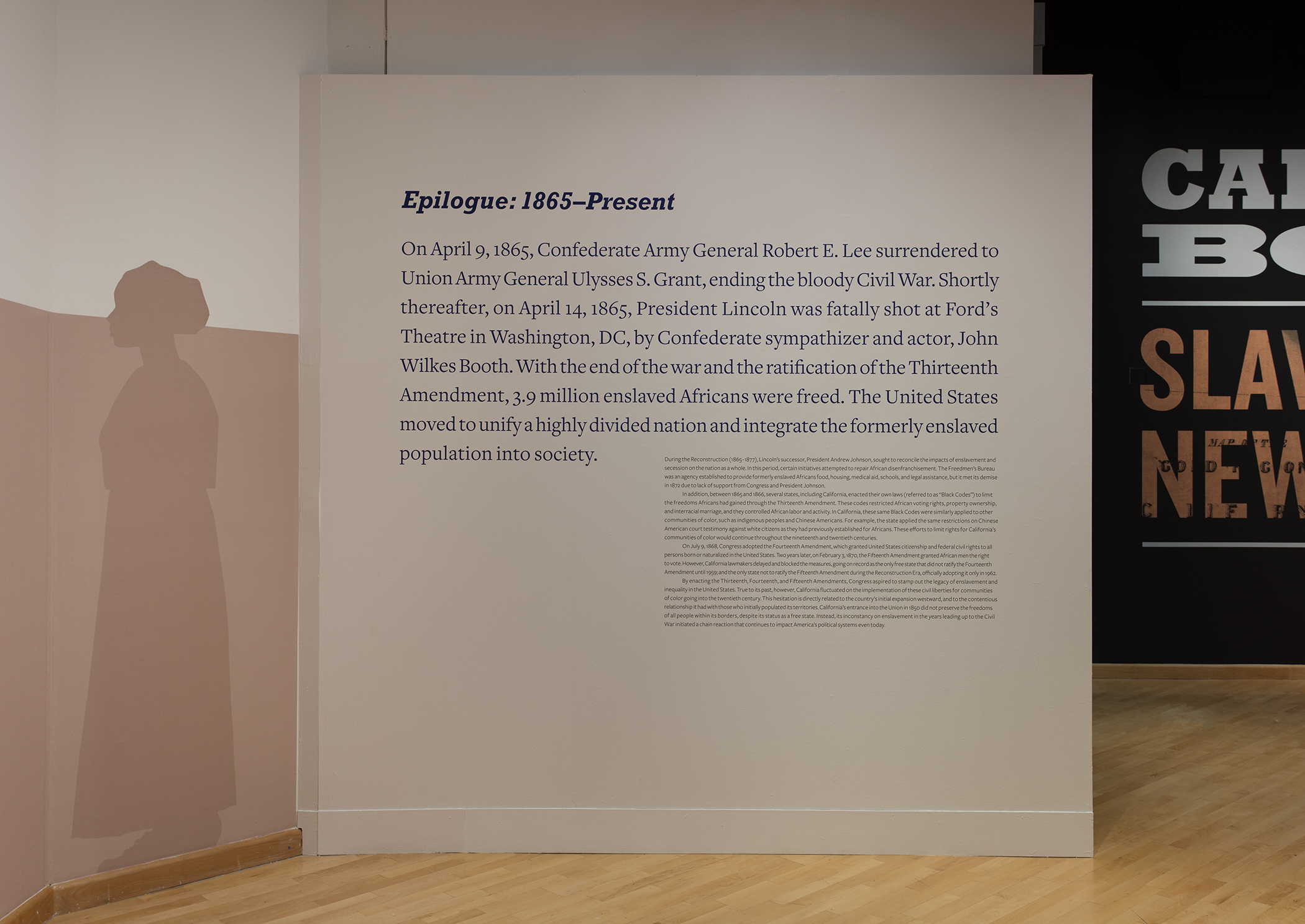

As droves of settlers from the North and South journeyed west seeking wealth and opportunity, the budding judicial system wavered on the issue of enslavement, leaving minorities in perpetual limbo. California entered into the Union as a free state as part of the Compromise of 1850, which triggered the strengthening of the national Fugitive Slave Law that allowed for the capture and return of runaway enslaved Africans even within the borders of free states. Soon after, California enacted its own Fugitive Slave Law in 1852, which allowed vigilantes to legally kidnap and re-enslave African people for financial gain.

Though this state law expired in 1855, the cases of enslaved Africans such as Archy Lee—a young laborer whose attempted re-enslavement challenged the bounds of the federal Fugitive Slave Law—incited political upheaval in the state that resonated throughout the nation. In the years leading up to the Civil War in 1861, California’s allegiance to the Union was tested through financial support, anti-enslavement legislation, and the ratification of the 13th Amendment, which abolished enslavement and involuntary servitude in 1865.

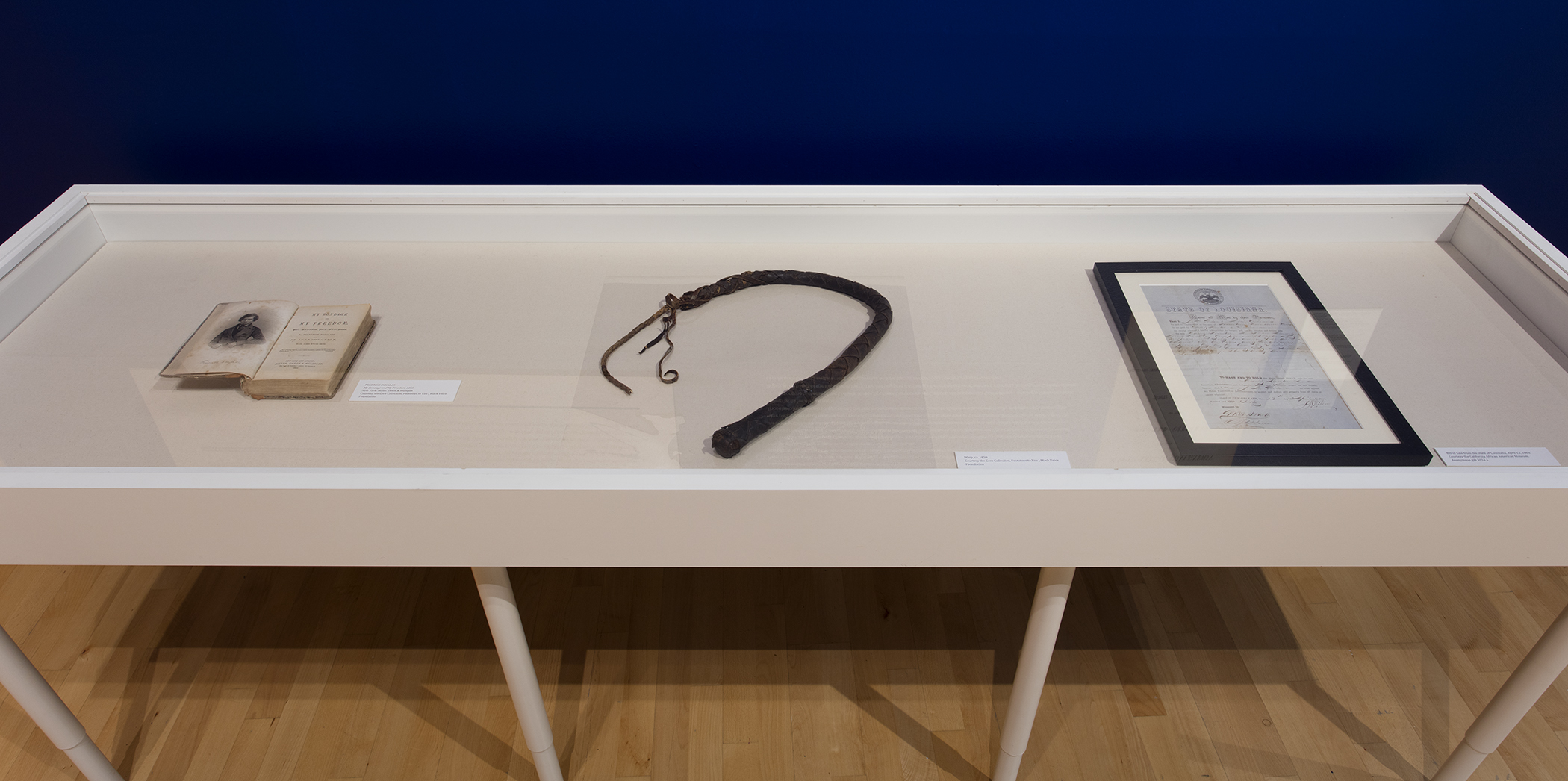

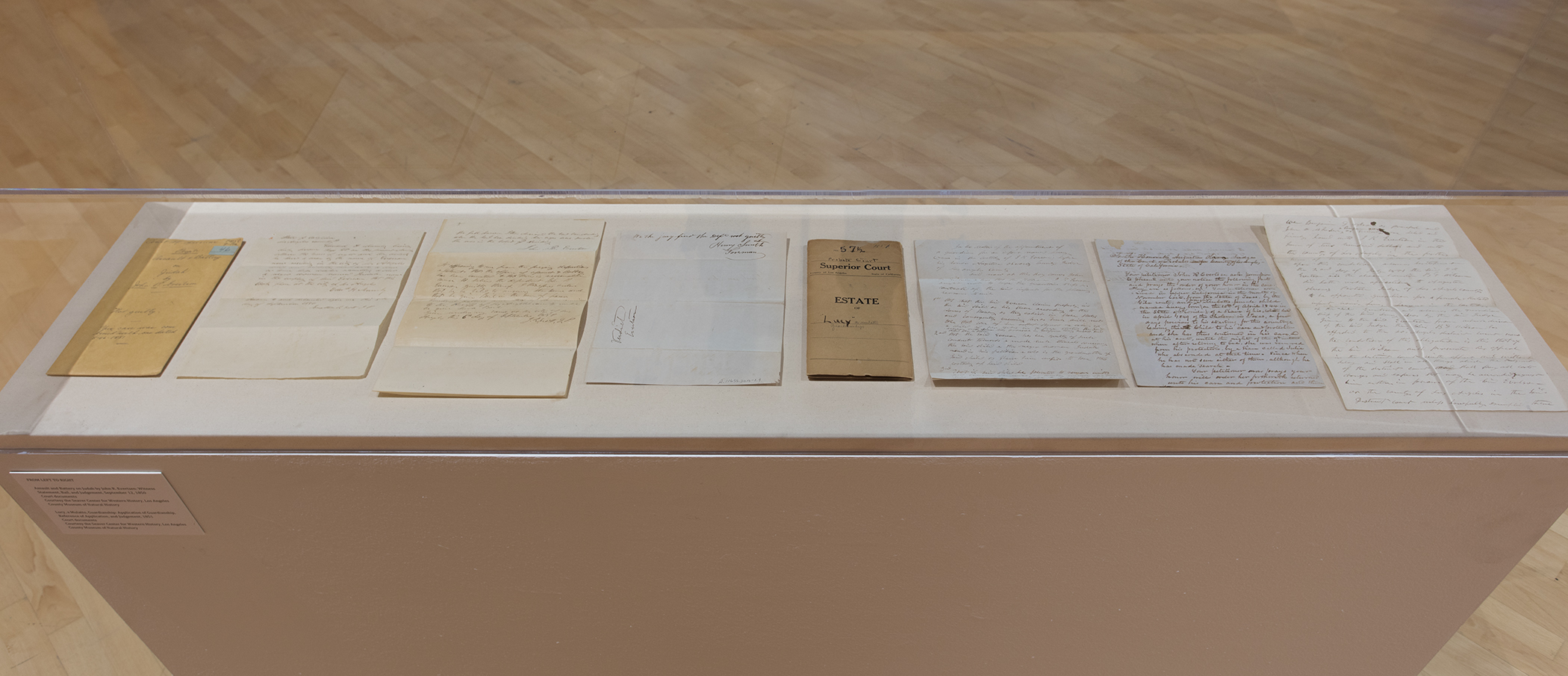

Using historical documents, rare artifacts, and other ephemera, California Bound: Slavery on the New Frontier, 1848–1865 illuminates how America’s expansion westward precipitated contentious relationships with those who populated its new territories. California’s entrance into the Union didn’t preserve the freedoms of people of color within its borders. Instead, the state’s vacillation on enslavement before the Civil War caused ripple effects in America’s political structures that are still being felt today.

This exhibition is curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager, and Taylor Bythewood-Porter, Assistant History Curator.

Special thanks to Dr. Stacey L. Smith, University of Oregon; Delilah Leonium Beasley; and the exhibition lenders.

Photos: Brian Forrest

Watch

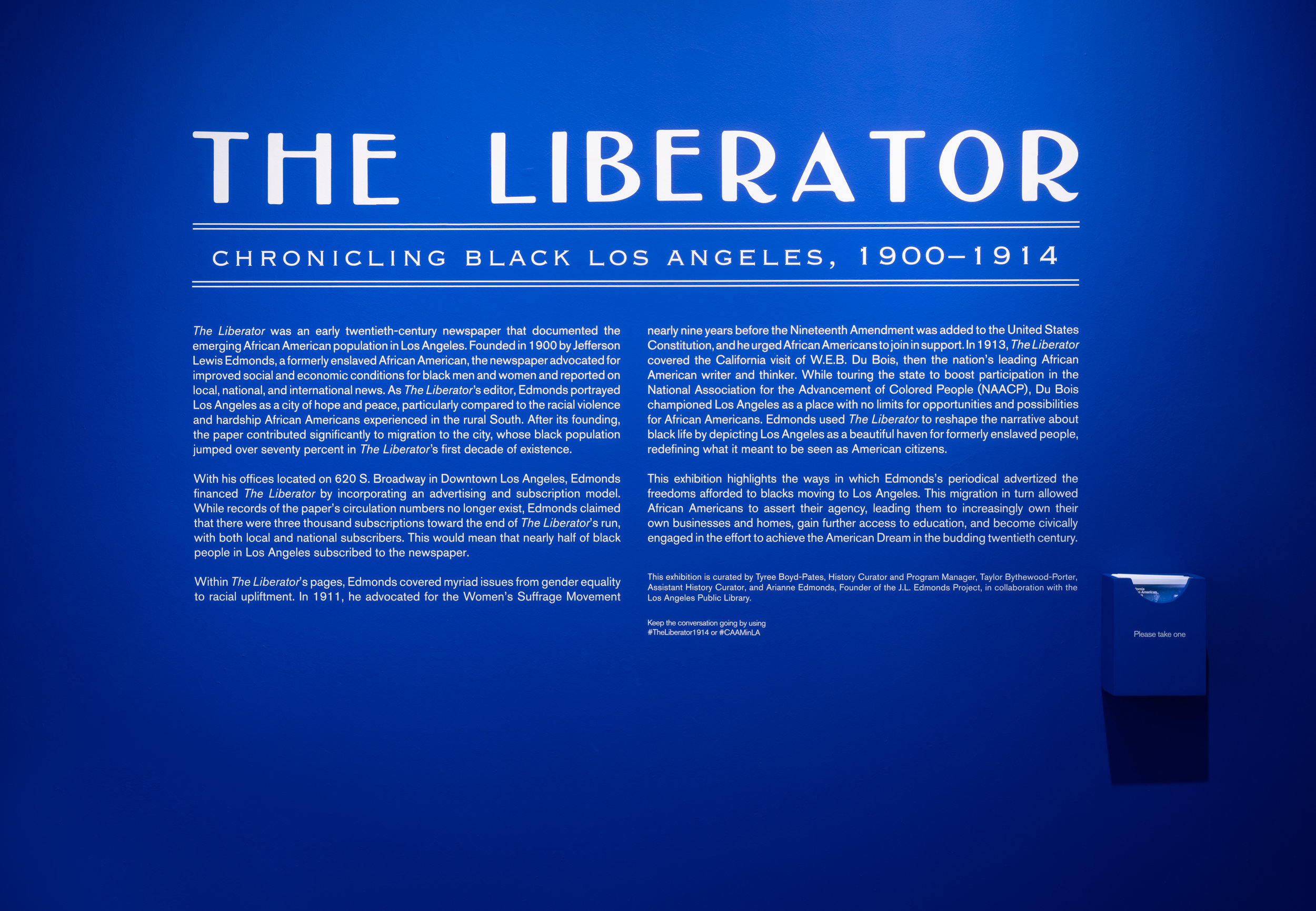

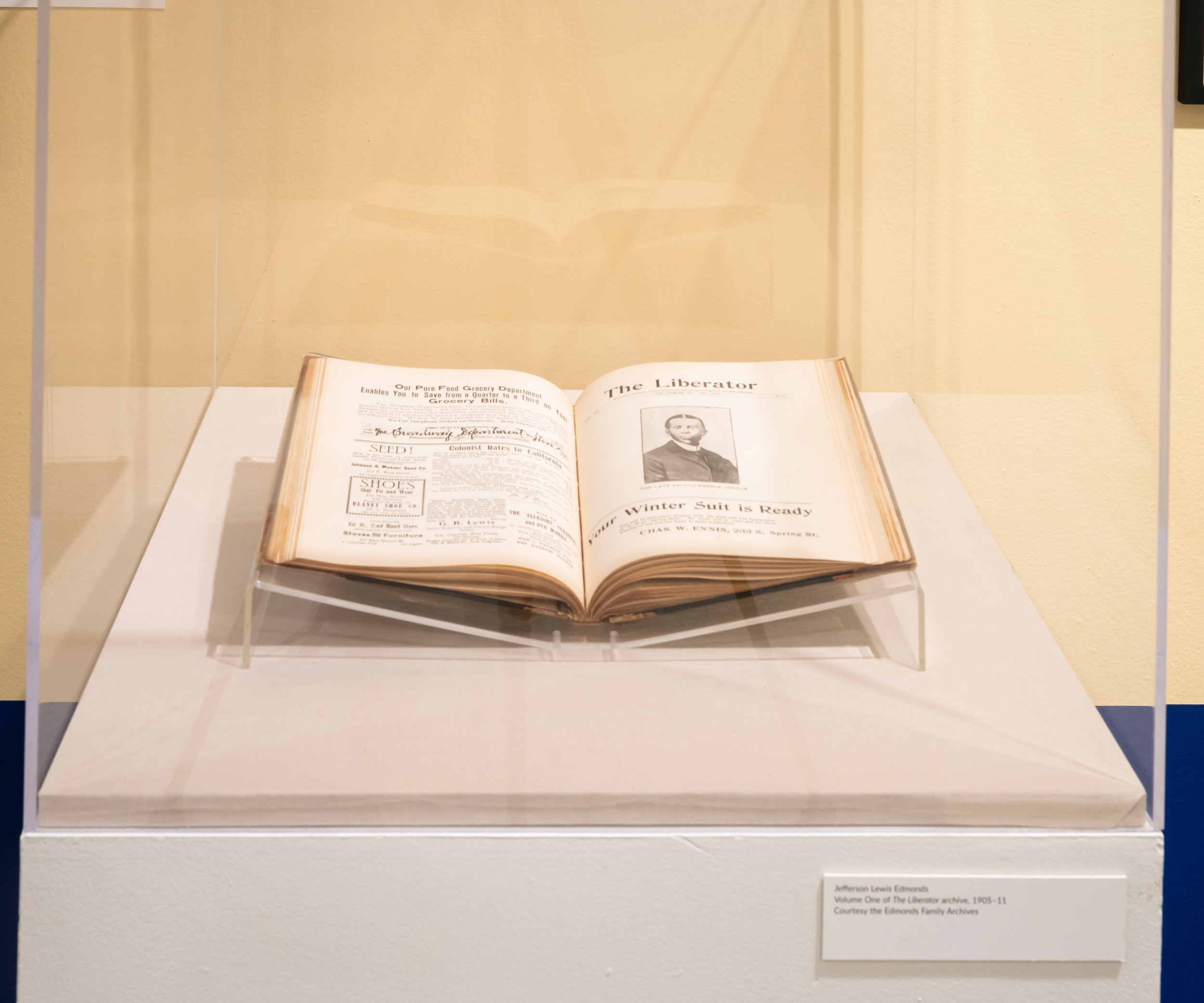

The Liberator: Chronicling Black Los Angeles, 1900–1914

‘The Liberator’ was an early twentieth-century newspaper that documented the emerging African American population in Los Angeles.

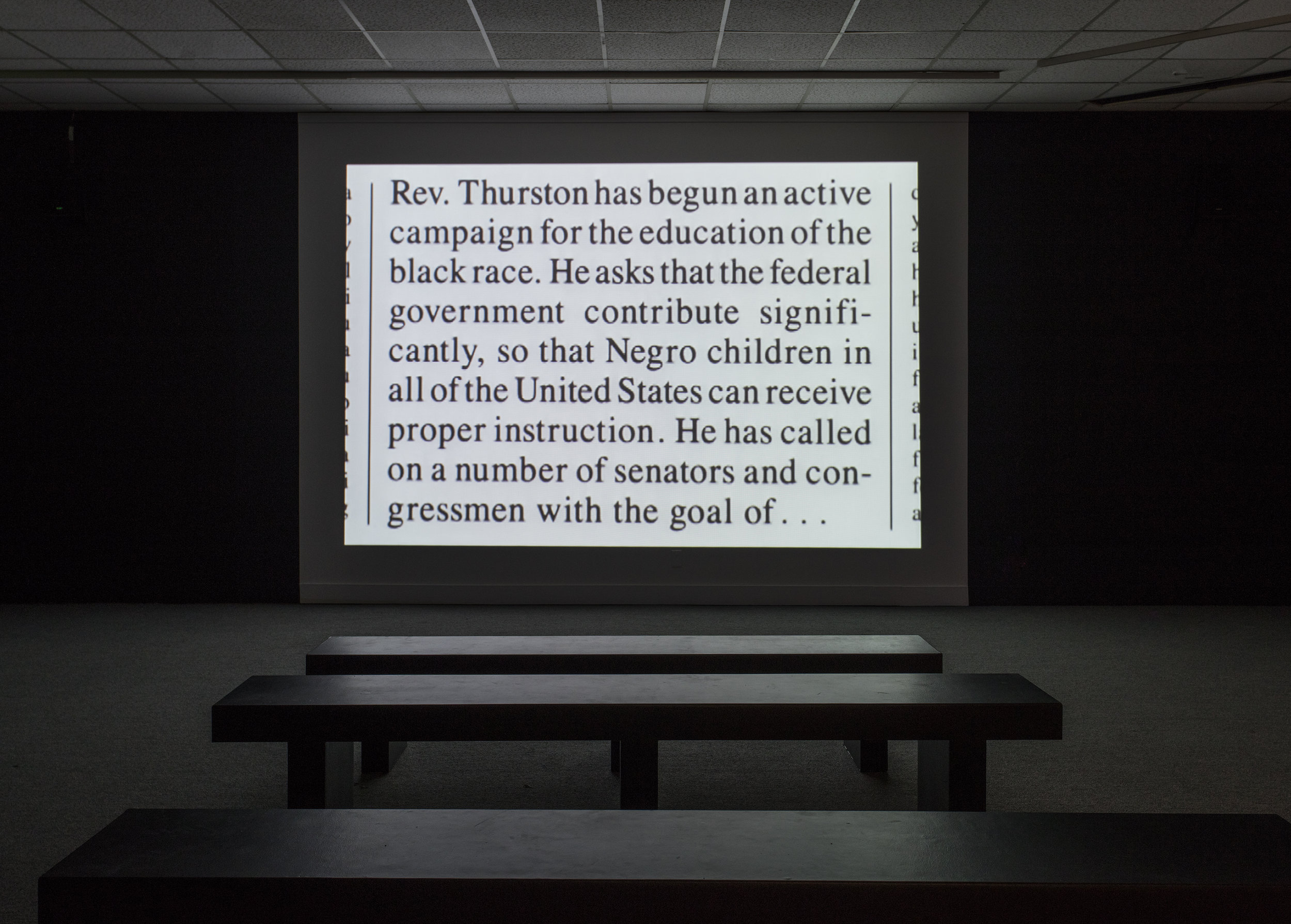

The Liberator: Chronicling Black Los Angeles, 1900–1914

Founded in 1900 by Jefferson Lewis Edmonds, a formerly enslaved African American, the newspaper advocated for improved social and economic conditions for black men and women and reported on local, national, and international news. As The Liberator’s editor, Edmonds portrayed Los Angeles as a city of hope and peace, particularly compared to the racial violence and hardship African Americans experienced in the rural South. After its founding, the paper contributed significantly to migration to the city, whose black population jumped over seventy percent in The Liberator’s first decade of existence.

With his offices located on 620 S. Broadway in Downtown Los Angeles, Edmonds financed The Liberator by incorporating an advertising and subscription model. While records of the paper’s circulation numbers no longer exist, Edmonds claimed that there were three thousand subscriptions toward the end of The Liberator’s run, with both local and national subscribers. This would mean that nearly half of black people in Los Angeles subscribed to the newspaper.

Within The Liberator’s pages, Edmonds covered myriad issues from gender equality to racial upliftment. In 1911, he advocated for the Women’s Suffrage Movement nearly nine years before the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the United States Constitution, and he urged African Americans to join in support. In 1913, The Liberator covered the California visit of W.E.B. Du Bois, then the nation’s leading African American writer and thinker. While touring the state to boost participation in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Du Bois championed Los Angeles as a place with no limits for opportunities and possibilities for African Americans. Edmonds used The Liberator to reshape the narrative about black life by depicting Los Angeles as a beautiful haven for formerly enslaved people, redefining what it meant to be seen as American citizens.

This exhibition highlights the ways in which Edmonds’s periodical advertized the freedoms afforded to blacks moving to Los Angeles. This migration in turn allowed African Americans to assert their agency, leading them to increasingly own their own businesses and homes, gain further access to education, and become civically engaged in the effort to achieve the American Dream in the budding twentieth century.

This exhibition is curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager, Taylor Bythewood-Porter, Assistant History Curator, and Arianne Edmonds, Founder of the J.L. Edmonds Project, in collaboration with the Los Angeles Public Library.

Photos: Elon Schoenholz

Watch

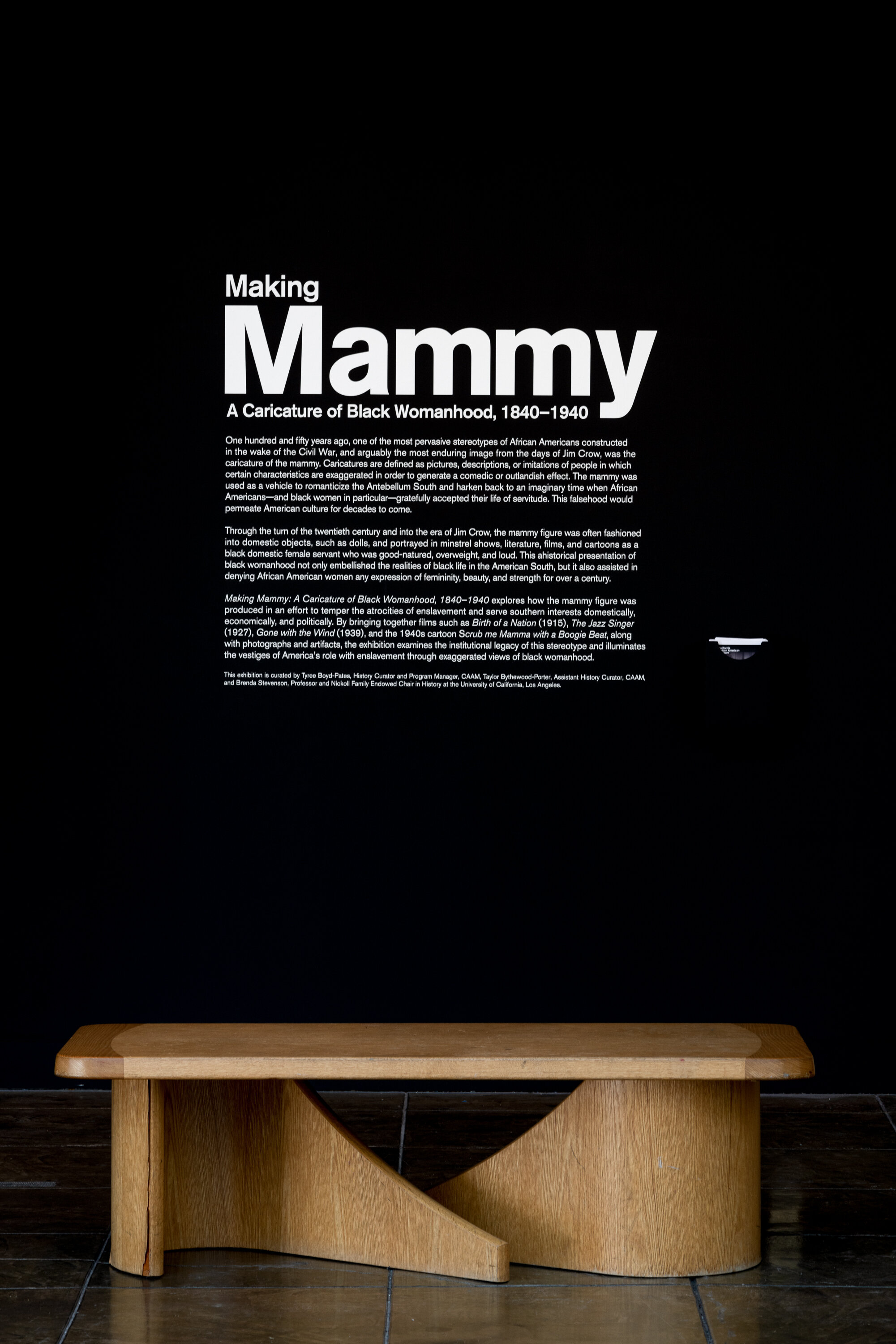

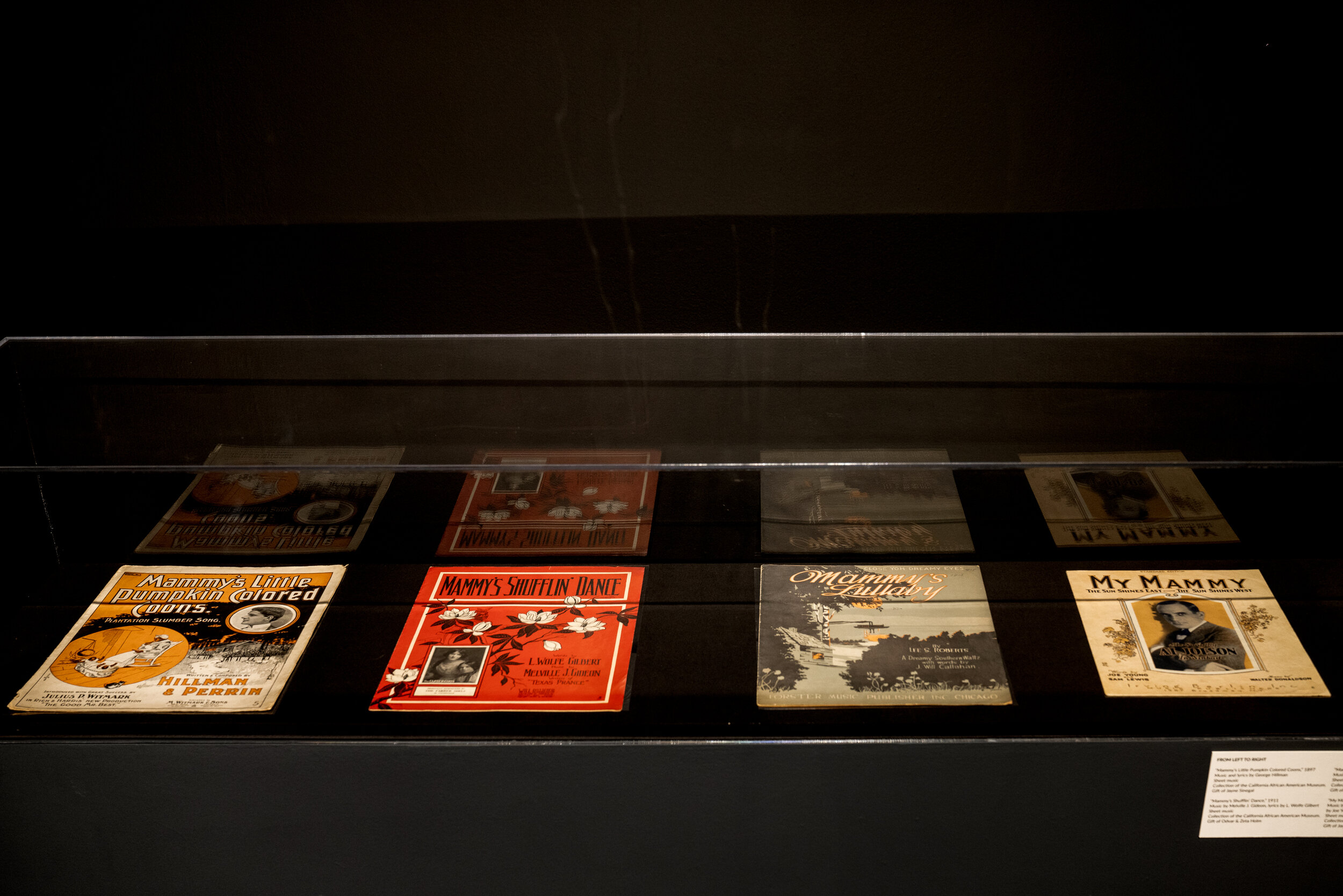

Making Mammy: A Caricature of Black Womanhood: 1840–1940

One hundred and fifty years ago, one of the most pervasive stereotypes of African Americans constructed in the wake of the Civil War, and arguably the most enduring image from the days of Jim Crow, was the caricature of the mammy.

Making Mammy: A Caricature of Black Womanhood: 1840–1940

Caricatures are defined as pictures, descriptions, or imitations of people in which certain characteristics are exaggerated in order to generate a comedic or outlandish effect. The mammy was used as a vehicle to romanticize the Antebellum South and harken back to an imaginary time when African Americans—and black women in particular—gratefully accepted their life of servitude. This falsehood would permeate American culture for decades to come.

Through the turn of the twentieth century and into the era of Jim Crow, the mammy figure was often fashioned into domestic objects, such as dolls, and portrayed in minstrel shows, literature, films, and cartoons as a black domestic female servant who was good-natured, overweight, and loud. This ahistorical presentation of black womanhood not only embellished the realities of black life in the American South, but it also assisted in denying African American women any expression of femininity, beauty, and strength for over a century.

Press

Making Mammy: A Caricature of Black Womanhood, 1840–1940 explores how the mammy figure was produced in an effort to temper the atrocities of enslavement and serve southern interests domestically, economically, and politically. By bringing together films such as Birth of a Nation (1915), The Jazz Singer (1927), Gone with the Wind (1939), and the 1940s cartoon Scrub me Mamma with a Boogie Beat, along with photographs and artifacts, the exhibition examines the institutional legacy of this stereotype and illuminates the vestiges of America’s role with enslavement through exaggerated views of black womanhood.

This exhibition is curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager, CAAM, Taylor Bythewood-Porter, Assistant History Curator, CAAM, and Brenda Stevenson, Professor and Nickoll Family Endowed Chair in History at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Photos: Elon Schoenholz

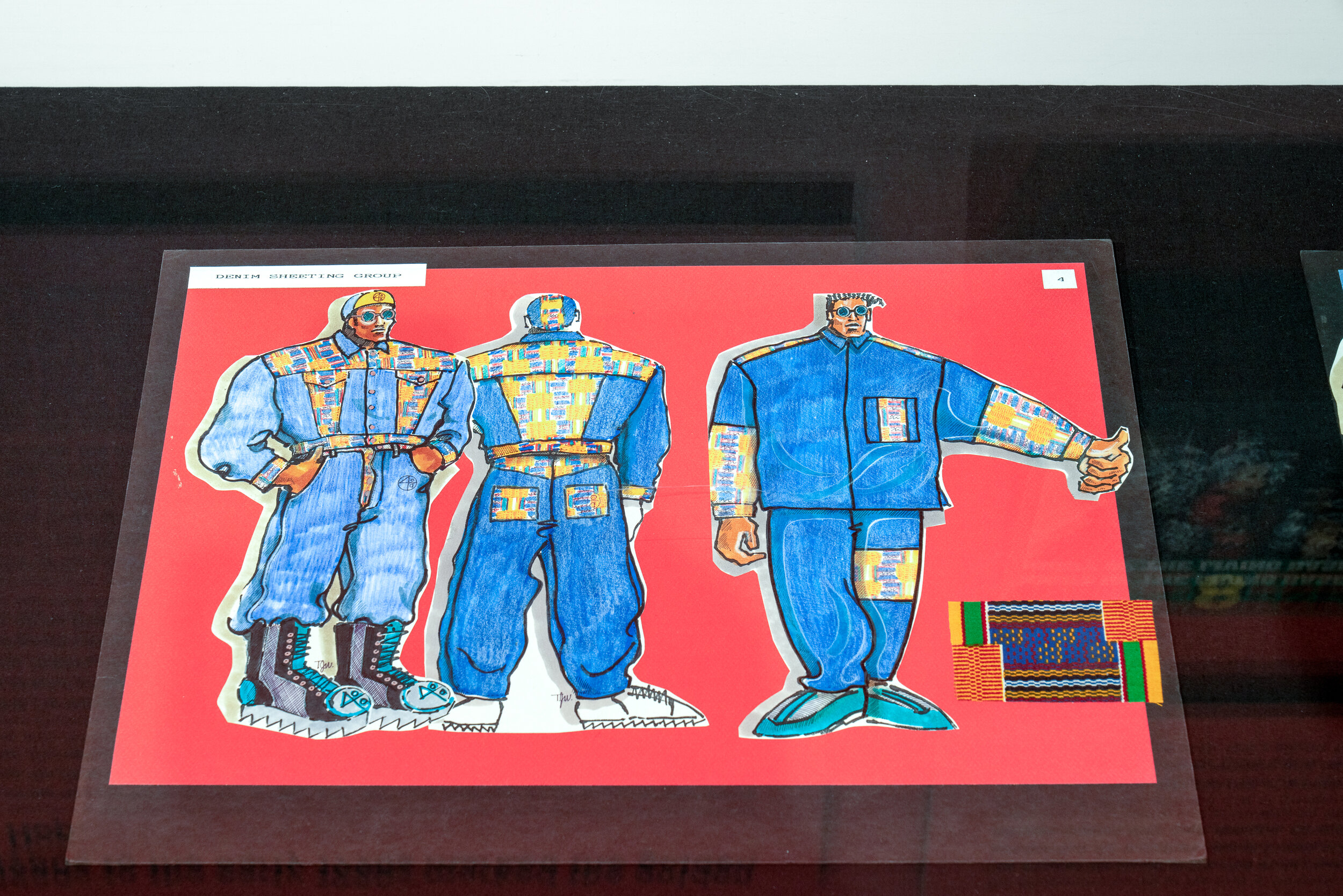

Cross Colours: Black Fashion in the 20th Century

Throughout the twentieth century, irrespective of class, fashion has been an effective political tool that African Americans have wielded to counter oppression, discrimination, and racism.

Cross Colours: Black Fashion in the 20th Century

Black Americans have used fashion as a form of racial pride, unification, and self-determination, reflecting shared ideologies. Cross Colours: Black Fashion in the 20th Century explores how black fashion, at the height of Hip Hop, reflected the social position and perspective of African Americans in the United States—especially in the 1990s, when the groundbreaking brand Cross Colours achieved its early commercial success.

In 1990, on the first season of the hit primetime television show The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, lead actor Will Smith wore a series of boldly hued and geometric looks designed by a budding Los Angeles–based urban apparel line. African American-owned, founded by Carl Jones and T.J. Walker, Cross Colours quickly skyrocketed, securing a plethora of orders across the country and breaking color barriers in the field of men’s apparel. The success of the young company, which Jones and Walker created for black youth with the premise of producing “clothing without prejudice,” had a significant influence on the mainstream fashion industry, inspiring it to take notice of the emerging importance of urban streetwear.

Cross Colours’s influence did not develop in a vacuum, however. Like so many African Americans before them, the brand’s co-founders felt the need to respond to intense social and political pressures that in turn influenced their approach to fashion. In particular, they sought to model black pride, community responsibility, and solidarity—causes rooted in Black Nationalist tendencies from earlier in the twentieth century, including Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa” movement of the 1920s; the Nation of Islam and its charismatic spokesman, Malcolm X, in the 1950s and 1960s; and the non-violent ethos of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement.

This exhibition also explores parallels between Cross Colours's emphasis on public engagement and the Black Panther Party’s advocacy for community outreach in 1970s Oakland. It likewise considers how adverse Reagan-era policies in the 1970s and 1980s influenced the birth of Hip Hop culture, with its embrace of Pan-Africanism and Afrocentrism. These elements were central to Cross Colours, whose pioneering vision brought a black urban aesthetic to mainstream culture and jump-started what is now a billion-dollar clothing industry.

Thirty years since its founding, the company continues to engage with contemporary socio-political movements and counter negative portrayals of black youth. The first exhibition to examine this groundbreaking brand, Cross Colours: Black Fashion in the 20th Century showcases vintage textiles, media footage, and rare ephemera that illuminate how Cross Colours has permeated popular culture and how fashion can be used to tell history anew.

This exhibition is curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates, History Curator and Program Manager, and Taylor Bythewood-Porter, Assistant History Curator.

Photos: Elon Schoenholz

WATCH